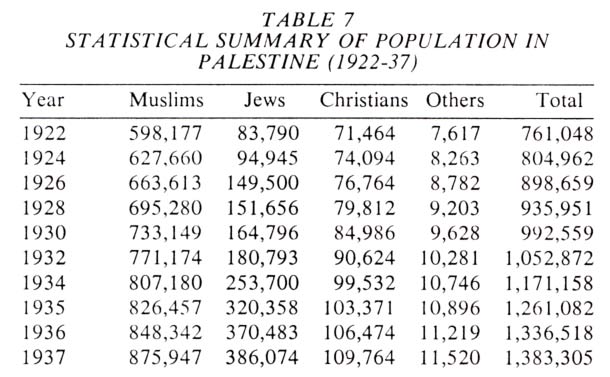

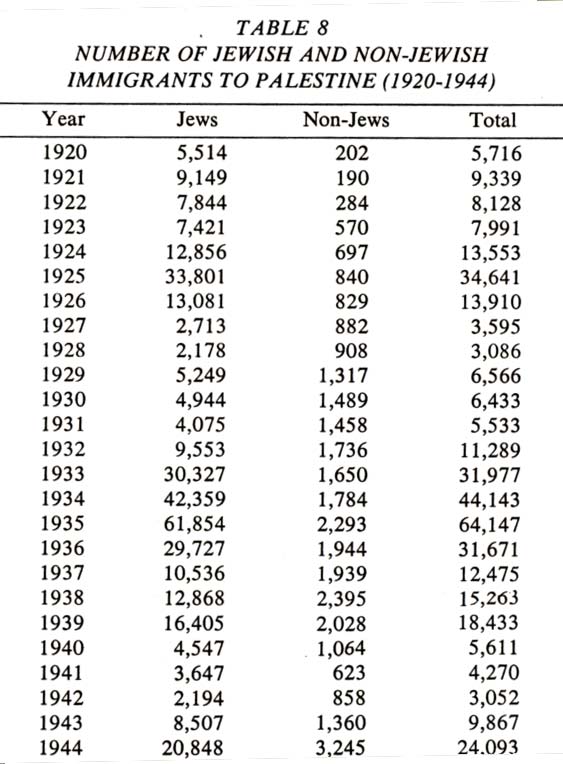

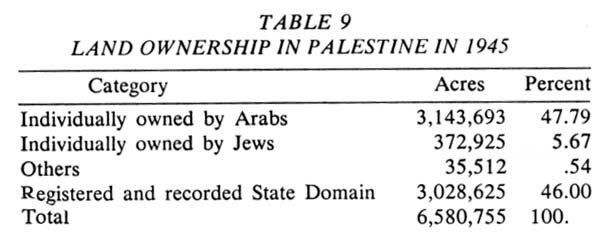

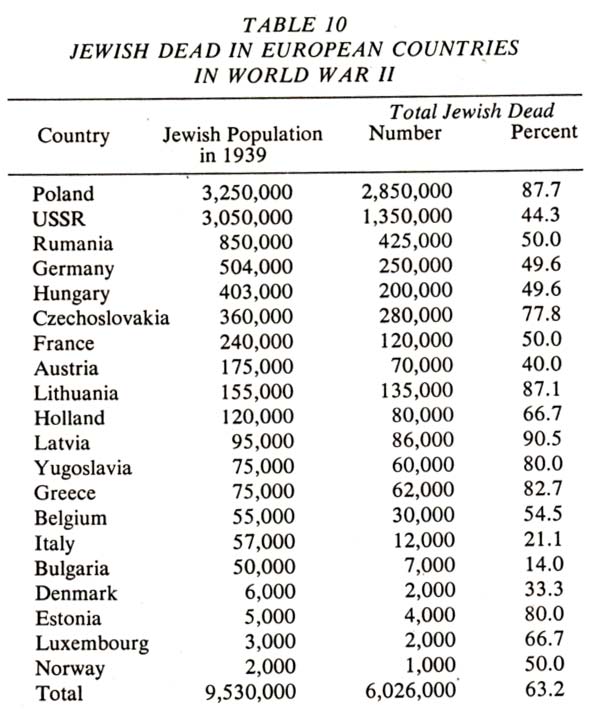

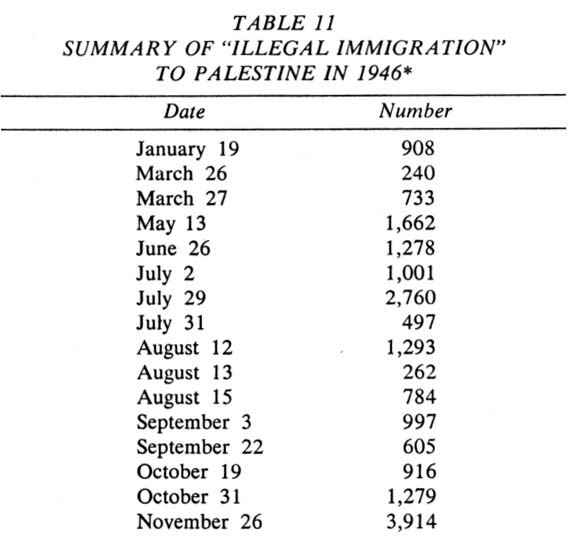

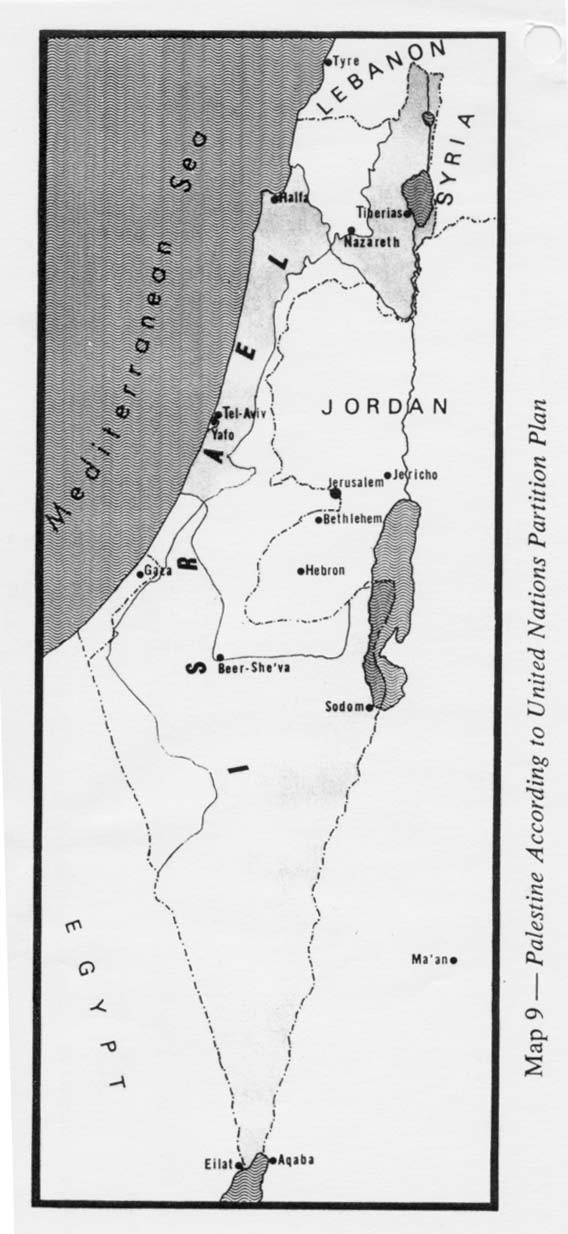

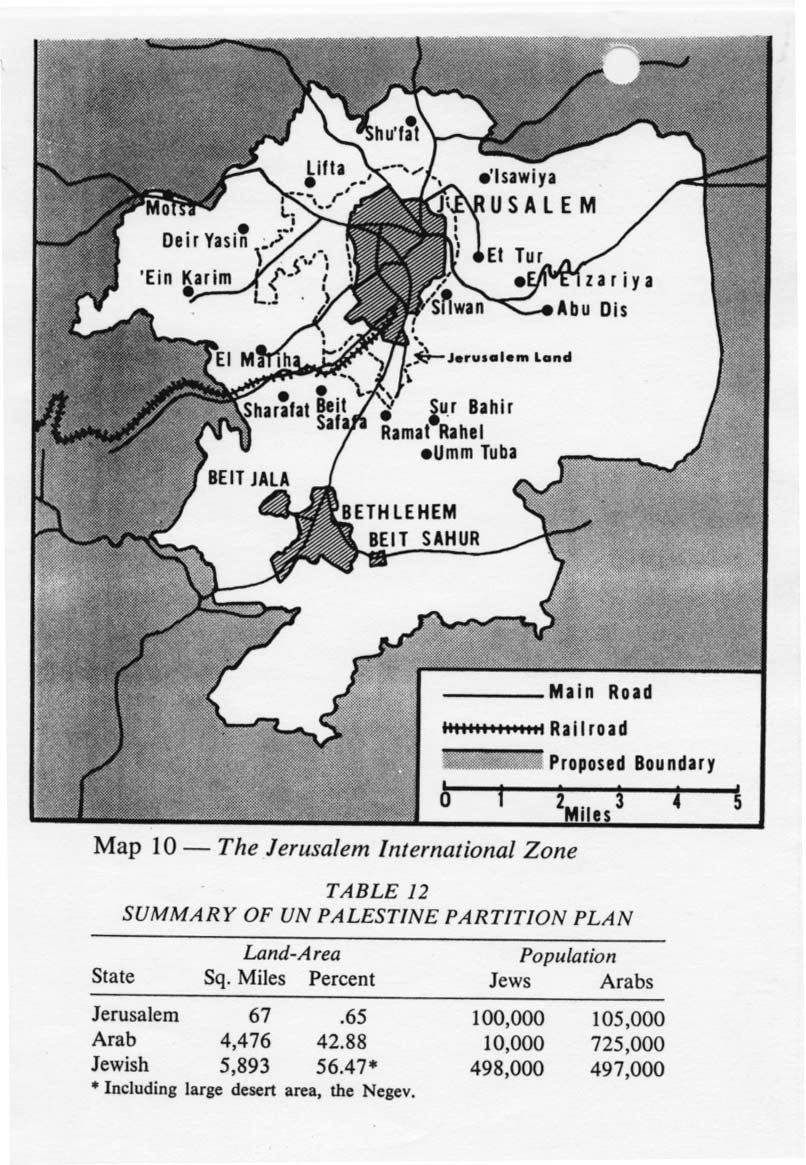

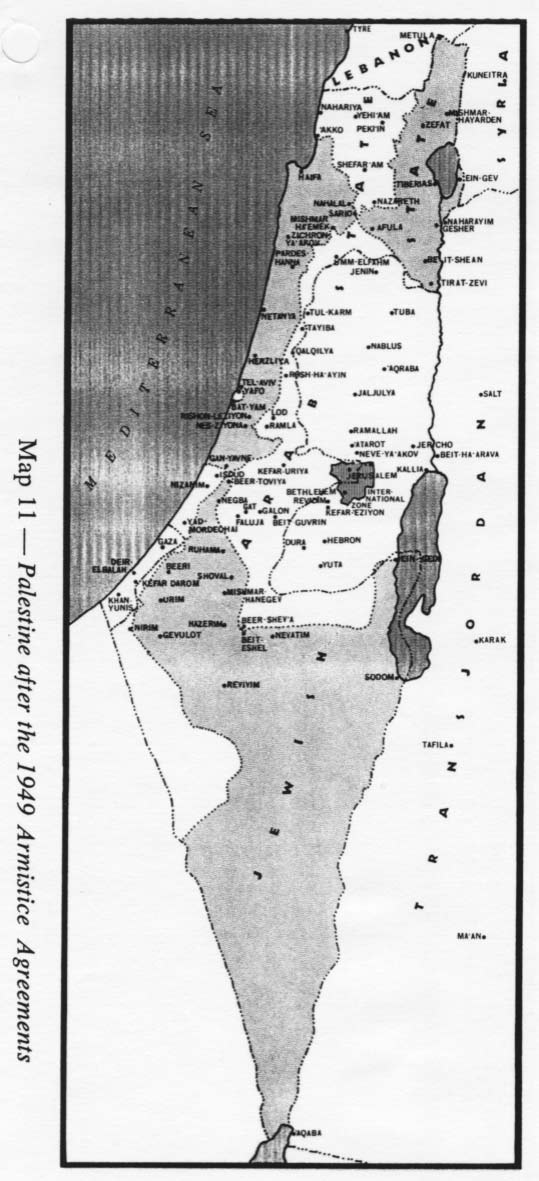

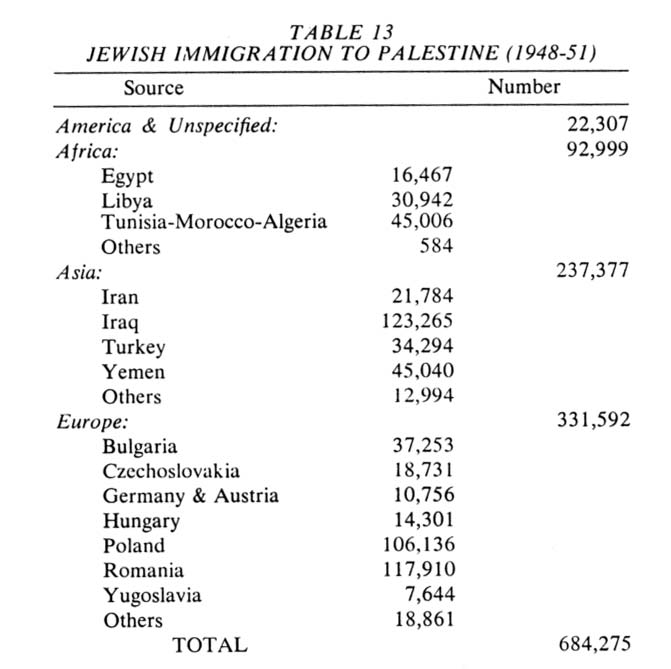

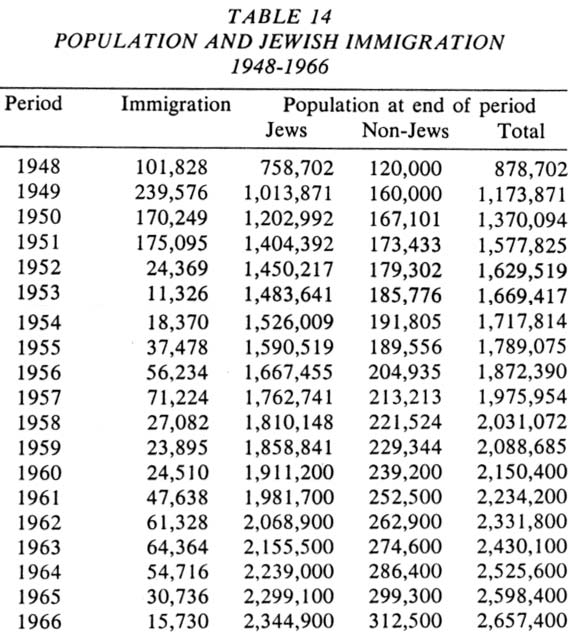

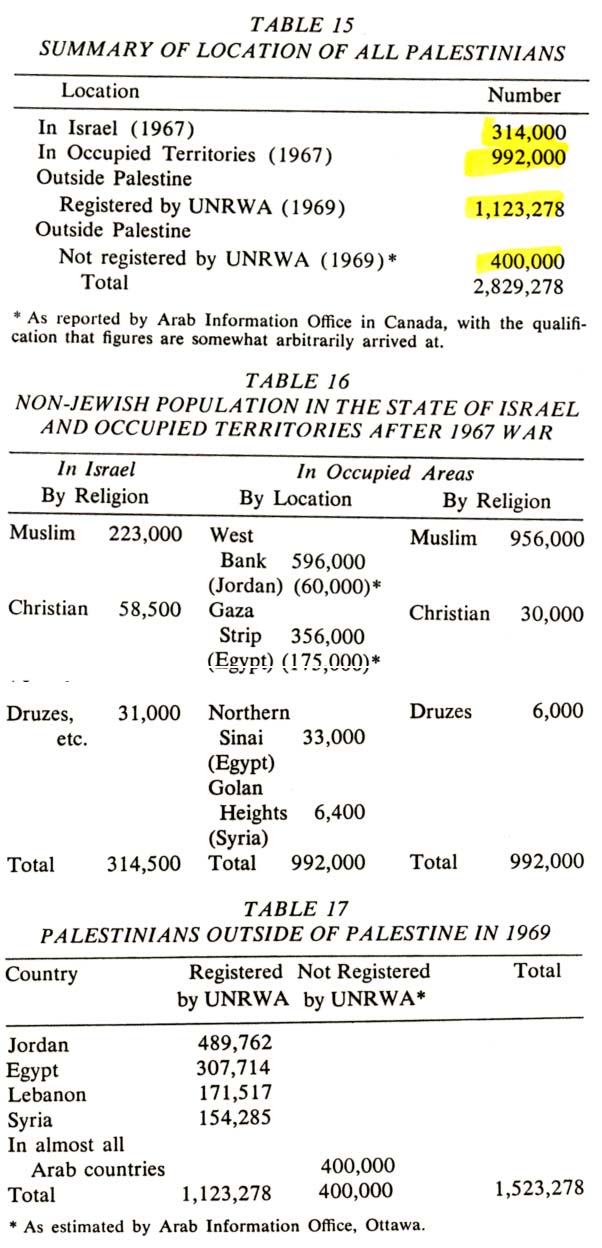

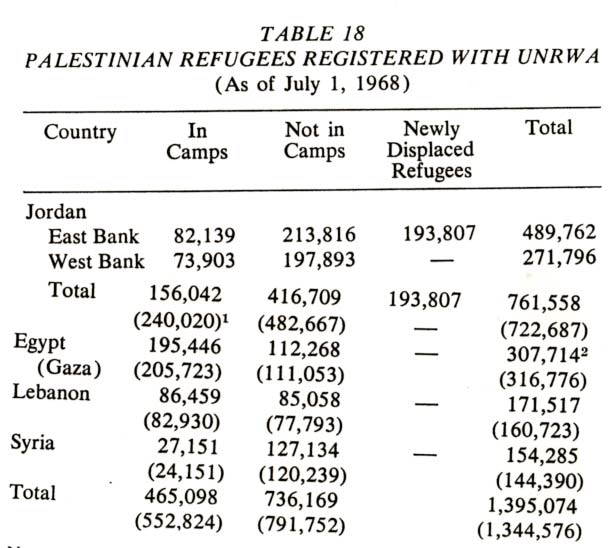

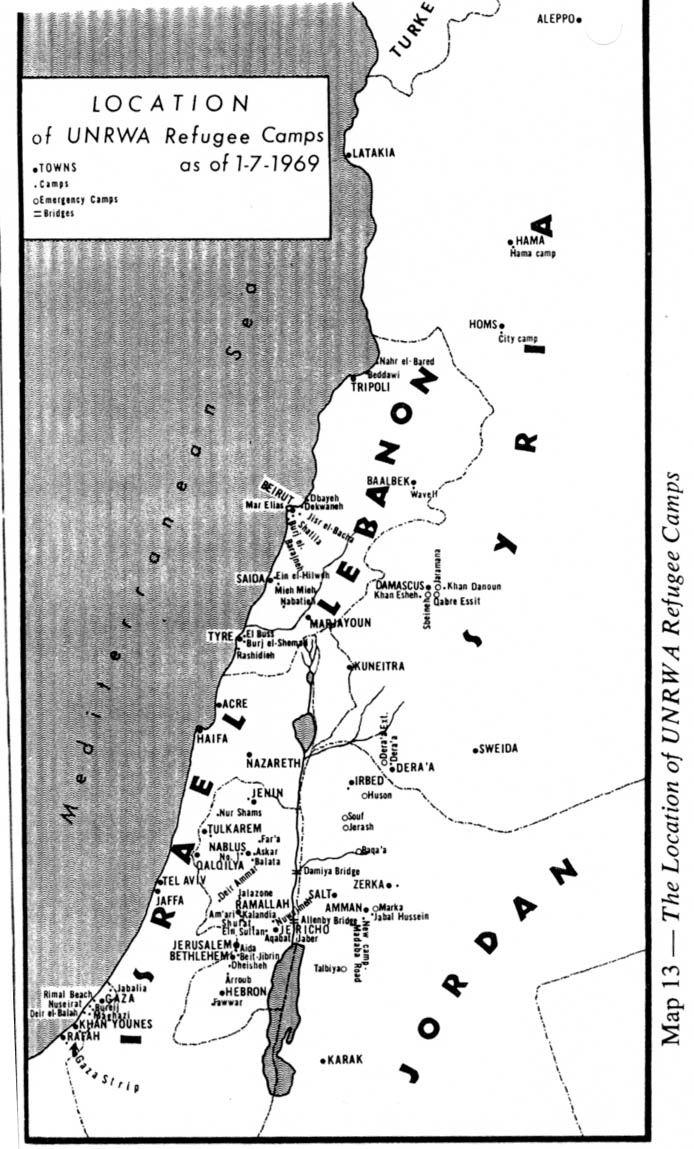

| The Arabs also have rights in Palestine; the Zionist program threatens those rights. Arabs will fight and die in their own cause. Kermit Roosevelt Precisely at the time when British imperialism, Protestant millenarianism, and Zionist ambition were reaching a new peak of fervor, Arab nationalism was also appearing as a determined and irreversible trend, destined to make itself felt throughout the Middle East. Neither the British nor the Zionists anticipated that they would feel this nationalism so soon or as strong as it turned out to be. It cannot be denied, of course, that the Arab world had been relatively docile for three centuries. Leading Arab thinkers referred to the era of Ottoman dominance as "the sleep of the ages," in which their world was culturally dormant, politically stagnant, and economically sterile. This sleep, no doubt, was one of the reasons why the West thought that the Arab could be ignored. But at that crucial point the West too was asleep, for it failed to recognize the extent to which the Arab world was already wide awake. The Arabs had been influenced and affected by both nineteenth-century European nationalism and the twentieth-century awakening of colonized peoples. When World War I came, they knew that they wanted their independence and their own nationhood. This meant freedom from the old domination, which was Turkish, and from the new intervention, which was European. They were expecting that the war would fulfill their wish, and in that hope and for that reason alone they had fought on the allied side. Thus it was a cause for considerable concern, if not alarm, when the Arabs saw decisions being made in London, Washington, and Paris that seemed to contradict the British promise of independence, especially since these decisions were being made without consultation with them. The Husseins and the Group of Seven did raise their voice in protest in Cairo, but then too quickly accepted at face value the assurances that were being given. Even General Allenby's entry into Jerusalem on December11, 1917 (Beersheba in the south and Jaffa on the coast hadalready been captured from the Turks) was reassuring forthe Arabs. While proclaiming the establishment of an administration under martial law, the British general guaranteed the protection of religious rights and properties for all, as follows: Since your city is regarded with affection by the adherents ofthree of the great religions of mankind. and since its soil has been consecrated by the prayers and pilgrimages of multitudes of devoted people of these three religions for many centuries, therefore do 1 make known to you that every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional right, endowment and bequest, or customary place of prayer, of whatsoever form of the three religions, will be maintained and protected, according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred. The new Occupied Enemy Territory Administration consisted of a chief, 13 district military governors (10 after 1919), 59 British assistants, and 17 appointed Arab officers. The chief quickly granted the traditional authority to existing religious institutions, including the Muslim (Shaira) courts, to administer their own affairs. A local Muslim council for the administration of endowment funds was appointed to replace the one in Constantinople. Arab Muslims thus had nothing to fear, and Arab Christians were not unhappy either. This early confidence in the British administration was soon to be undermined, however. Early in 1918 the administration authorized a Zionist commission to travel, investigate, and report on the prospects in Palestine of a national home for the Jews. Upon the completion of its work, the commission asked for Jewish representation in the occupying administration, and this request was granted. The Zionist group also proposed the appointment of a land commission, consisting of experts to be nominated by themselves, to ascertain the resources of Palestine, and claimed the right to select Jewish members for the police force. More than that, the commission insisted that Jews be granted freedom to train their own defense forces, which training was already in progress. The Zionists were active not only in Palestine but also in Paris, where the Arabs too were determined to assert their rights. But when their representatives arrived in the French capital, they learned that the Zionists had arrived before them. Both parties tried to persuade the great powers of their point of view, although there also appears to have been at least a temporary rapprochement between Arabs and Zionists. In March of 1919 Chaim Weizmann and Emir, later Prince, Feisal of Iraq reached an agreement that Arabs and Zionists should cooperate in the development of Palestine. Feisal assured the Jews "a most hearty welcome home," while Weizmann promised that "the Arab peasant and tenant farmers shall be protected in their rights.": The agreements between the two leaders, however, turned out to be of no consequence, since both sides found them unacceptable, and when Feisal tried to assert himself as king of an independent Greater Syria he was soon thrown out of Damascus by the French. Meanwhile the French and British could not agree on the full meaning of the Sykes-Picot accord. Consequently; Dr. Howard Bliss, president of the Syrian Protestant College and spokesman with the Arabs, proposed that an inter-allied commission be sent to the Lebanon-Syria-Palestine area to determine the governmental wishes of the local population. Both the French and British were reluctant to ask the Arabs, and so the United States alone sent Henry C. King and Charles R. Crane--they became known as the King-Crane Commission - to conduct the public opinion poll. The Arab nationalists took advantage of the presence of the Americans and convened a general congress in Damascus in July, 1919 with delegates from the Ottoman province areas of Syria and Palestine. The congress unanimously demanded "full and absolute independence for Syria" (including Lebanon, Palestine, Trans--Jordan, and Cilicia). The congress also rejected Zionist claims to Palestine, and requested that, if a Mandate government was absolutely essential, the trusteeship be granted to either the United States or Great Britain, in that ord". France was completely ruled out as a possibility. The King-Crane Commission noted the Arab, position, but talked also to Jewish representatives. After hearing both sides. King and Crane came to the conclusion that the establishment by the Zionists of a homeland for the Jews really meant or would lead to the expulsion of the Arabs. They said: The fact came out repeatedly in the commission's conference with Jewish representatives, that the Zionist looked forward to a practically complete dispossession of the present non-Jewish inhabitants of Palestine by various forms of purchase. This chilling report on Zionism, however, was not taken seriously in the United States, mainly because the Zionists had an effective lobby against it. Thus it happened that in April 1920, France and Britain had their way concerning the mandates at the conference in San Remo. Lebanon and Syria were assigned to France, and Britain got Palestine, the boundaries of which still needed to be clarified. At this point the limits of Palestine were only vaguely defined. The Zionists wanted a large Palestine. They were bidding for a national home that included territories beyond the Jordan River, at least up to the Hijaz Railway. The first draft of the Mandate, therefore, included both sides of the Jordan River, including the area later known as Transjordan. Though this bid was not granted, the Zionists never forgot it, and maps of Eretz Israel, published after the 1967 war, included this area along with the occupied territories as part of Israel. Britain did not bow to full Zionist demands but rather made a concession to the Husseins. In 1921 Abdullah Hussein wasrecognized the emir of Transjordan, and the Mandate draft was withdrawn to exclude this new emirate from the territory in which the Jewish national home was to come into being. Though the national home had, literally, been narrowed down, the Mandate for Palestine as it was finally ratified by the Council of the League of Nations on September 29, 1923, was generally in favor of the Zionists. Quoting the Balfour Declaration in its preamble, the Mandate acknowledged the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine, as well as the grounds for "reconstituting" the national home in that country. While the Arabs were not once mentioned by name in the entire Mandate, Article 4 provided for the establishment of a Jewish Agency, working hand in hand with the Palestine government in matters affecting the establishment of the Jewish national home, an agency that was already operative before the Mandate officially sanctioned it. American Zionists, led by Louis Brandeis, had contributed their share to the wording of the Mandate but the United States government's position still remained somewhat ambivalent. In 1922, Congress passed a resolution, again as a result of Zionist pressures, favoring the establishment of a national home for the Jews in Palestine, but America's official policy of neutrality was emphasized in the Anglo-American convention of December 1924, when the United States insisted that all international agreements affecting Middle East mandated territories provide for equal American economic opportunity. From that time on American-owned oil companies obtained many concessions in the region, and that is why the United States eventually took on much of the British political burden in the area. The Arabs appeared to submit to all these decisions being made in foreign capitals about them and their territories without their being asked, but in their hearts they were not accepting what was going on. Arab nationalists, who had attended the Syrian Congress, now formed Muslim-Christian Associations in the Arab towns of Palestine to protest the establishment of the Jewish national home. The Associations met in a country-wide conference at Haifa in December of 1920 and called for the founding of an independent Arab state, in which all the residents of Palestine would be citizens. In 1919 the population included about 65,000 Jews, many of them Arabized Jews of long standing, and ten times that many Arabs, about 650,000, of whom some 70,000 were Christians, the balance being Muslims. The first official non-Ottoman census taken by the British administration in 1922, as well as later similar counts, revealed substantial -increases, as can be seen in Table 7. The increases were due to the high Arab birth rate on the one hand, and the high Jewish immigration on the other hand.  In the meantime, Arab protests against Zionist policies had become violent. On Easter Sunday, 1920, five Jews were killed and 200 injured in Haifa. A military committee of inquiry determined that the outbreak was caused by Arab nationalism, which was now being threatened by Zionism. A year later Arab attacks on Jaffa resulted in the death of 47 Jews and the wounding of 146 others. These protests and attacks were spontaneous actions of citizens and not coordinated by any central political or military force. Again, Zionism was found to be the cause of the outbreak, but, since the irritation was not removed, these violent clashes were only the beginning. The Arabs were well aware that not only Jewish extremists but also the responsible representatives of Zionism were deliberately and carefully planning for a future Palestine in which Jews would be the majority. Zionist progress in this direction did not suffer when the military administration was replaced by a civil government on July 1, 1920. Sir Herbert Samuel assumed the office of high commissioner. He was supported by an executive council and an advisory council consisting of ten nominated non-officials, of whom four were Muslim Arabs, three were Christian Arabs, and three were Jews. The small influence of a Jewish minority in the administration was offset by the influence that the Jewish Agency had with the British themselves. In less than a month, the first immigration ordinance was passed authorizing a quota of 16,500 immigrant Jews for the first year. The next governmental development was an order to strengthen the Muslim organization. The Supreme Muslim Council was then created for the purpose of administering the Awqaf, the religious endowments of the Muslims and the Sharia religious courts, which had formerly been administered from Constantinople. The mufti (Muslim judicial official) of Jerusalem became the head of the Supreme Council. This development, however, did not satisfy the Arabs nor did it deter them from voicing their main grievance - that their independence was being denied them by the mandatory powers and being taken away by the Zionists. On February 21, 1922, a delegation of Arab leaders appeared in London to inform Secretary of State Winston Churchill that they could not accept the Balfour Declaration or the proposed Mandate and that they wanted their independence immediately. They insisted that the Palestinian government should be responsible only to the Palestinian people. It would provide for the creation of a national independent government in accordance with the spirit of the covenant of the League of Nations. This government would safeguard and guarantee the legal rights of foreigners, the religious equality of all peoples, the rights of minorities, and the rights of the assisting power. In the face of Arab pressure the British government issued a White Paper to interpret the Balfour Declaration to both the Arab delegation and the Zionist organization. This explanation, while it reaffirmed the Declaration, denied that it meant making Palestine "as Jewish as England is English" or that Britain had had in mind "the disappearance or the subordination of the Arabic population, language, or culture in Palestine." The terms of the Declaration, it was further explained. did not mean "that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home," but only that such a home should be "founded in Palestine." The home did not mean "the imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine," but rather the development of a center in which Jews could take an interest and a pride. For the fulfillment of this policy, it was believed necessary, so said the White Paper, to increase by immigration the size of the Jewish community in Palestine. Soon thereafter, in order-in-council was issued by the British providing for the creation of a legislative council, consisting of the high commissioner and 22 members, 10 official and 12 elected (eight Muslim, two Christian, and two Jews). The Arab delegation. still in London, insisted again that only a constitution, which would give "the people of Palestine full control of their own affairs," could be acceptable to them. Mr. Churchill replied that the creation of a national government at that point would prevent the British from fulfilling their pledge to the Jewish people. Hearing this reply, the delegation concluded that the undertaking to provide a Jewish national home was the reason why Arabs were being denied their rights in Palestine and why Palestine could not have an independent government the same as Iraq and Transjordan. They also concluded that self-government would not be granted until there were Jewish people sufficient in number to satisfy the Zionists. Later events supported the delegation's conclusion. Jewish immigration proceeded as planned. The 5,000 and more who arrived in the last four months of 1920, nearly doubled to just under 10,000 in 1921. In the three years of 1924-26 nearly 60,000 arrived, largely as a consequence of economic difficulties in Poland. Even higher immigration peaks were reached in the 1930s after Hitler came to power in Germany (see Table 8)  The 1922 British White Paper had stipulated that immigration limits were to be determined by "the economic absorptive capacity of the country." but absorptive capacity meant one thing to the Jews and quite another thing to the Arabs. The Jewish Agency, rather well financed by international Zionism, saw to it that the land absorbed the Jewish immigrants, but in the process many Arabs lost the lands for which they and their ancestors had been working for many years. Whose the lands actually were became a matter of considerable debate as the years went on. Both Jews and Arabs were telling the world that all they wanted was to live in their country, in their own homes, and on their own lands. Both claimed historic rights to these lands. The resolution of all the conflicting claims was made difficult in part by the poor records of surveys and ownership that had been kept during Ottoman days. According to the best records available, however, Jewish ownership of Palestine land was only about two percent in 1922. This was increased to about 5.67 percent in 1945 (see Table 9). This represented registrations in old and defective  land registers, but these acres of land could not easily be found on the ground without overlapping with other property that had been identified and claimed. Similarly, the Arab figure could have been increased by 52,925 acres of good land for which the Sultan held the title, but which the tenants really assumed to be theirs by right of freehold tenure. The so-called state domains were not all purely state domains. Land thus identified included government buildings, forest preserves, road and railway allowances, as well as marshes and waste lands. In addition, there were cultivable lands held only nominally by the state. Arab farmers living on then possessed hereditary cultivation rights. and paid annual rental or tax. The state domains also included lands uncultivable by ordinary means but used by village people for grazing their livestock or for fuel gathering. Some cultivators could make a living, though a very meager one, by terracing small pockets of soil among the rocks and planting olive shoots. The Arab farmers had managed through the years to cover vast hillsides, rich in rocks but poor in soil, with olive orchards, and they owned 99 percent of the olive trees in the country, not an in-significant fact considering; that most of these were in the stony hills. Another block of uncultivable land in the state domain included the Negev with its 2,643,844 acres. On this land lived some 90.000 nomads whose tribes had grazed their flocks there from time immemorial. The rights of the nomads had never been challenged, and so government ownership was only “presumed.” The Jewish Agency obtained land mainly from two sources: purchases from absentee landowners and grants from state domains. The Arab tenants did not always suffer when land changed hands, but more often than not they did. Tenants who had been on particular lands for generations were often evicted by the new owners to make room for Jewish immigrants. For the Jews the "economic absorption capacity" was always more than adequate; for the Arabs it had already passed the limit. While some of the private lands were sold by Arab landlords voluntarily for pure economic reasons and without humanitarian considerations for the tenants, other owners were pressured to sell, since the new land and tax rules made continuous absentee ownership a burden. When the owners became willing to sell, the Jewish Agency stepped in and purchased the land at bargain prices. Sometimes the prices paid were very high. Tenants were often evicted soon thereafter. As Sami Hadawi reports: In one instance, over 40,000 acres, comprising 18 villageswere sold, resulting in the eviction of 688 Arab agricultural families. Of these, 309 families joined the landless classes, while the remainder drifted either into towns and cities or became hired ploughmen and laborers in other villages. Although eviction took place in 1922, the problem remained with the Palestine government to find land for some of these displaced persons until the termination of the mandate in 1948. The creation of large numbers of landless Arabs made the meaning of the Balfour Declaration very clear. The establishment of a national home for the Jews could only result in the destruction of the national home of the Palestinian Arabs. For this reason, the Arabs could not see themselves cooperating with British plans for the Jews to any degree, and they rejected election in the legislative council. They also refused to accept nomination to an advisory council that was subsequently proposed. The British Mandatory government could not give up its attempt to "democratize" the administration, and so it tried next to establish an Arab agency to operate on a par with the Jewish Agency. The Arab agency would be consulted on such matters as immigration, since on this matter "the views of the Arab community were entitled to a special consideration." The Arabs declined this offer as well, on the grounds that the agency would not satisfy the aspirations of the Arab people. As far as they were concerned, the Jewish Agency had no status either, since the Arabs of Palestine had never recognized it. Having made the proposal, the high commissioner felt that he had no alternative but to continue governing exclusively with the aid of British officials. As the 1920s came to a close the restlessness and agitation on the part of the Arabs decreased slightly. Their passivity at this point was mainly due to the drop in Jewish immigration due to the economic depression. While the population was not increasing as expected, the Jewish agricultural communities in Palestine were developing remarkably. The same was true of the cities. Modern suburbs were appearing in Jerusalem and Haifa. Tel Aviv showed the most growth of all. A village of 2,000 in 1914, the coastal city a decade later had a population of 30,000. Small industries were springing up everywhere. The school system was flourishing, including the Hebrew university, which was founded in Jerusalem in 1925 to promote Hebrew as one of the three official languages of Palestine along with Arabic and English. Balfour himself had come from England to participate in the ceremonies opening this new school. In the development of the Jewish community, the Jewish Agency did not forget its Hagana (defense) arm. The activities of these police units dated back to the 1870s, when the first of the new Jewish colonies had been founded in Palestine. After World War I the original Hagana Hashamen (defense watchmen) were organized into a paramilitary organization to recruit, train, and equip all able-bodied men and women to assist the long-term purposes of the Jewish Agency and the Zionist Organization, the establishment of a Jewish state. The Arab community too developed and progressed as new roads were built, education was promoted, new agricultural techniques were introduced, and new markets established. In one decade the export of citrus fruits alone increased threefold to 2,610,000 cases in 1930. Most of the citrus plantations were owned by Arabs. The growing prosperity, however, did not decrease dissatisfaction with developments generally. On the contrary, by 1930 Arabs felt more keenly than ever that independence and control of their own destiny was further away than it had been at the time of the 1915 revolt against the Ottoman empire. A dozen years had now passed since the end of the war. The feelings concerning the lost cause were so sensitive that the slightest incident could touch off major disorders. Such an incident had occurred in 1929, at the Wailing Wall, believed to be a fragment of Herod's temple, which in turn had been built on the site of the temple of Solomon. On the Day of Atonement, the Jews had introduced a screen to divide men and women during prayers. The Muslims, who had not been consulted, objected to this regulation on the grounds that the Jews were preparing to take gradual possession of the Mosque of Al Aksa by starting with control of this wall. The National Council of the Jews denied this, but Arab nationalist agitators had once more been aroused. A Jewish demonstration, in the course of which the Zionist flag was raised and the Zionist anthem sung, was followed by an Arab counter-demonstration. These acts in turn led to murderous attacks on Jews in various parts of the country. The Jews suffered 133 dead and 339 wounded. The British police, on the other hand, killed about 116 Arabs and wounded 232 others. A British commission of inquiry visited Palestine and reported that Arab fears for their economic and political future were the cause of the violent outbreak. The fears were not unfounded. A Zionist Congress in Zurich had just announced that a strong body of wealthy non-Zionists would join the Zionist endeavors and provide funds for further Zionist activities in Palestine. The commission recommended that the British define clearly what the Balfour Declaration and Mandate meant when they talked about safeguarding the rights of the non-Jewish communities, and that it clarify the policies of immigration and land tenure in relation to these rights. Immigration, said the commission, should be controlled to prevent the excesses of 1925-26, and the eviction of peasant cultivators from the land should be checked. Finally the 1922 statement specifying that the Zionist Organization would not share to any degree in the government of Palestine, should be implemented. Soon thereafter the newly formed Arab Executive asked the British government to cease immigration, to declare Arab lands inalienable, and to establish a democratic government with representation on a population basis. The British were unwilling and declared that such demands required changes incompatible with the demands of the Mandate, but it had to do more than just say no. On August 6, 1930 His Majesty's government issued another White Paper trying to satisfy both sides, but after conferring with Zionist leaders it assigned a larger role for an enlarged Jewish Agency. For the Arabs this was a clear sign that the Zionist lobby in London carried more weight than the wishes of the Arab population in Palestine. It was clear that there was more trouble ahead, and it came in spite of remarkable prosperity and development in Palestine in the early 1930s, while the rest of the world was sunk in depression and stagnation. Arab disturbances in 1933 were directed not so much against the Zionists as against the British who, the Arabs were sure, were favoring the Zionists in their policies. In 1934 the Arabs formed five political parties, which together went to the high commission asking for the establishment of a democratic representative government, the prohibition of the transfer of Arab land to Jews, and an end to Jewish immigration until a competent committee had determined the absorptive capacity of the land. Again, the administration refused to accept anything that interfered with the Mandate, meaning with the Balfour Declaration. It promised, however, to make another attempt to establish self-governing institutions under the Mandate. The proposed legislative council would have 28 members, 11 of which would be Muslim, seven would be Jews, and three Christian. The council would have considerable powers, although final policy on immigration should be decided by the high commission. This time the Arabs, though not entirely happy, were ready to talk. The Zionists rejected the proposal and also persuaded Parliament that the power the Arab majority would gain would be inconsistent with the Balfour Declaration. The Arabs again saw evidences of the strength of the Zionist lobby and maintained, as they had in 1931, that Jewish influence was responsible for the Arabs not being granted their rights. The representatives of the five Arab parties were invited to London early in 1936 once more to discuss constitutional matters, but developments in Palestine prevented their going. The country was shaken on April 15-16 by major disturbances and the murder of Jews by Arabs and then of Arabs by Jews. The political parties now gave themselves to forming national committees in all of the Arab towns and villages, and on April 21 they called a general strike. The purpose of the strike was to force an end to Jewish immigration, which in 1935 had reached an all-time high of over 65,000, with an increased displacement of Arab cultivators. The Arabs were now wide awake politically. A Supreme Arab Committee, later known as the Arab Higher Committee, was established with the mufti of Jerusalem as president. Christian Arabs were as prominent in the development as were Muslim Arabs in all the political parties. The Arab Higher Committee expanded the strike, which already paralyzed transport, construction, and shopkeeping, to include refusal to pay taxes. The British, however, seemed not yet to have faced up to the fact that the Arabs were wide awake and that they had legitimate grievances. Another royal commission was appointed "to ascertain the underlying causes of the disturbances," as if these causes were not already known. Meanwhile, the revolt against the Mandate government and Zionism spread from passive strike to military action in the hills. Pipelines were punctured, roads were mined, railway tracks were torn up, and Jews were murdered. The British brought in two divisions to bring the revolt under control, and before it was over, the official list of casualties listed 314 dead and 1,337 wounded, most of them Arabs. In addition it was estimated that 1,000 Arab rebels had been killed by police, troops, and Hagana forces. The strike was finally called off by Arab leaders in October, but the end of resistance was not in sight. On the contrary, the year had introduced a new arena of Arab action. In 1936, for the first time, the Palestinian cause brought a reaction from Arab governments outside Palestine. Although they had been sympathetic before, it was not until a change in international status of several Arab states that they intervened.The Arab states at this point included the independent Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which had close ties with Britain. The independent Kingdom of Iraq, also in treaty relationship with Great Britain, was ruled by the Hashemites, bitter enemies of the Saudis. The small state of Transjordan, an artificial creation of Britain, was autonomously administered by a Hashemite prince, supervised by Britain. He too was an enemy of the Saudi family. The two republics of Syria and Lebanon were administered by France. Yemen was an independent state, as was Egypt, though the latter was tied to Britain as was Iraq. The stature of Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon were all improved in 1936 by treaties negotiated with Britain and France. All three states now had greater freedom of action in international affairs. While a recognized national and international status was thus being achieved, domestic rivalries were bringing ill will to the Arab world, and for a while it seemed that the states would never get together. Emir Abdullah, the Hashemite prince of Transjordan, was aspiring to the establishment of a Greater Syria (Iraq-Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Transjordan), according to the British pledge to Hussein, which Abdullah insisted had been postponed but not aborted by the World War I peace settlement. The dissolution of the Mandate, he felt, would bring him and his state the desired fulfillment. Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud of Arabia was opposed to such a scheme and formed a close relationship with the majority party in Syria. Britain seemed to be sympathetic to Saud's scheme oil the assumption that it would make more Arab friends for Britain than would the Hashemite dream. Egypt also supported Saud, hoping itself to become the leader of the emerging block.All of these rivalries threatened to abort Arab unity, but the Arab rebellion in Palestine gave a new lease on life to pan-Arabism, though not immediately, Iraq, playing up to Britain, twice asked the Arab Higher Committee to call off the strike. The Arab leaders of Palestine responded by saying that they would prefer joint mediation by all the monarchs of all the independent states. Accordingly, the monarchs of Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Iraq, and Transjordan got together and asked the Arabs to call off the strike, promising them that Britain would do justice to the Arab people of Palestine. The Arabs of Palestine listened and again gave Britain more trust than she had earned. They assumed that Britain would find a solution acceptable to the Arabs. The pressure on the British was relaxed, but the Arab governments were now subjected to constant popular pressure in the form of resolutions, demonstrations, and "Palestine Days" to insist that Britain fulfill its promises. The British solution was anticipated in the findings of the Peel Royal Commission published in June 1937. Peel confirmed that the 1936 revolt was caused by the same factors that had brought about the disturbances in 1920, 1921, and 1933, namely, the Arab desire for national independence and the fear of the Jewish national home. The Commission concluded that the Arab claim to self-government and the Jewish national home were mutually exclusive, a fact that both Arabs and Zionists had known all along. To resolve the conflict, the Commission recommended partition of Palestine, creating a Jewish state in the northern and western regions and incorporating the balance of Palestine into the territory of Transjordan. The Arab Higher Committee rejected the partition plan and opposed any surrender of Palestinian territory to the Zionists. Some Palestinians close to Abdullah were prepared to accept it. A pan-Arab Conference on September 8, 1937, on the other hand, supported the Arab Higher Committee and declared that Palestine was Arab and its preservation was the duty of every Arab. The Zionist Congress of 1937, not surprisingly, favored the establishment of the Jewish state, and authorized negotiations. In the meantime the Council of the League of Nations had appointed a commission to submit a partition plan of its own. The result was a report in October 1938 that division was practically impossible without creating a Jewish state in which at least 49 percent of the population would be Arab. Meanwhile the British government also came to the conclusion almost at the same time that the political, administrative, and financial difficulties arising from partition would be so great as to make the plan impracticable. At that point the British decided to call another London conference to discuss the situation with both Arabs and Jews, the latter represented by the Jewish Agency and other outside Zionist leaders. The Arabs were represented by the Higher Committee and by the governments of Egypt, Iraq. Saudi Arabia, and Yemen. The Arabs refused, however, to meet together with the Jewish Agency, which they had still not recognized. The result was that two conferences, one Anglo-Arab and the other Anglo-Jewish, were held in February andch 1939. At the Anglo-Arab Conference the Arabs demanded an interpretation of the McMahon-Hussein correspondence of 1915-16. The delegates maintained that Palestine was one of those countries to which independence had been promised. The British conceded that the Arab interpretation had "greater force than had appeared hitherto" but declined officiallyto accept the view. An Anglo-Arab committee studying theMcMahon-Hussein correspondence came to the conclusion that His Majesty's Government were not free to dispose ofPalestine without regard for the wishes and interests of the inhabitants of' Palestine and that these statements must be taken into account in any attempt to estimate the responsibilities which-upon any interpretation of the correspondence-His Majesty's Government have incurred towards those inhabitants as a result of the correspondence. Unofficially, the British had gradually become ready to admit that the concept of the Jewish national home violated the rights of Palestine Arabs. Another White Paper issued in May 1939 admitted as much when it said that it was not part of the British policy "that Palestine should become a Jewish state." Still trying to appease both sides, the British also insisted that the McMahon correspondence did not form "a just basis for the claim that Palestine should be converted into an Arab state."The British expressed the hope that within ten years an independent Palestine state, in which both Arabs and Jews would share in the government, could be established and the Mandate withdrawn. On matters of immigration, the White Paper announced a policy that related immigration not only to economic capacity but also to political tolerance. Expressing the view that the commitment of the Balfour Declaration had been fulfilled, the British insisted that henceforth Jewish immigration would be limited to what the Arabs could tolerate. Now it was the Zionists' turn to be furious, and the 1939 World Congress said that the Jewish people would not acquiesce to a minority status. The Arabs too were critical, but at least they were beginning to see some fruits of their long years of agitation. In Palestine, meanwhile, the violent hostilities of 1936 were repeating themselves in 1939, with no less than 3315 incidents of violence reported, including 230 attacks of the police, 130 attacks on Jewish settlements, and 94 incidents of sabotage. Arab and Jewish guerrillas were both in operation. At the end of the year 98 Jews were dead and 159 wounded; the Arabs counted 414 dead and 373 wounded; the British 7 dead and 66 wounded. The military court tried 526 persons, 544 Arabs, and 74 Jews. Fifty-five Jews were sentenced to death. It was the intention of the British to seek approval for its latest White Paper policy from the Council of the League of Nations, but before it could do so war broke out and the League came to an end. With the results of the war, the situation in Palestine became worse than ever; and the British wanted out more than ever. In the end they were forced to place the problem into the lap of the newly formed United Nations. The resolution adopted by the General Assembly on November 29, 1947 provided not for simple partition with economic union. It envisaged the creation of an Arab state, a Jewish state, and the City of Jerusalem its a corpus separatum under a special international regime administered by the United Nations. -Count Folke Bernadotte The White Paper of May 1939 was believed by the British government to be a step leading toward the solution of the Palestine problem; but whatever potential it may have had for the resolution of the conflict, it was soon overtaken and made of no effect by the arrival of World War II, the ensuing Nazi holocaust, and the resulting developments in both the Jewish and Arab worlds. Consequently, after World War II the big powers determined the future of Palestine through a new international forum, the United Nations. The war created even more Jewish refugees who wanted to go to Palestine and an even stronger Zionist determination to establish the Jewish national home than had been noted in the 1936s. It also increased Arab nationalism and pan--Arabism with the concomitant desire to have Arabs alone, as individual states or as a union of states, determine the course of events in the Arab world. Months before World War II ended it became evident that the Arab states were destined to occupy a key position in the power politics of the post-war period. Beyond developments in the Jewish and Arab worlds new dimensions appeared in the international power play of the big nations. While Palestine presented Britain with a most unwanted burden, she was by no means ready to give up her interests in the Middle East. Indeed, the 1939 White Paper concessions to the Arabs may be interpreted as an attempt to strengthen Britain's hold on, or access to, the Arab Middle East for its strategic geographic value and its oil resources. Both of these Middle East assets were also the chief reasons why World War II drew both the United States and the Soviet Union more firmly into the Middle East arena. Both states gave ideological reasons for their interest and involvement, but the practical realities were that no aspiring world power could afford to bypass the geopolitical middle of the earth, around which the whole world seemed to turn, and the holy oil indispensable to the smooth running of the imperial wheels. The coming of the war in September 1939 had the immediate effect of temporary tranquility in Palestine as both Palestinian Jews and Arabs rallied to the British cause. The Jews were initially recruited for military service by the Jewish Agency, but this arrangement was dropped when the Agency objected to the employment of Jews in military duties outside the Middle East and in military units containing both Arabs and Jews. Thus, only 27,000 of the 134,000 Jewish recruits between the ages of 18 and 40 entered the British services. The more numerous Palestinian Arabs provided fewer than half the Jewish number, though they too served the British cause in significant ways. The reason for the Jewish Agency's desire to keep the troops close to home can be seen in its great unhappiness with the policies of the British Administration after May 1939. The Zionists were determined not to lose any ground - they rather hoped to gain some - in their movement toward the long hoped-for Jewish national home. Any opportunities in that direction arising from the new situation were to be exploited to the maximum. This meant, among other things, an accelerated buildup of the Hagana (defense) forces. The new access to military equipment and training helped to make this possible. By 1946 Hagana numbered 60,000 men, and all were well equipped. Parallel to this well-armed Hagana organization were two splinter military groups, the Irgun Zvei Leumi (National Military Organization) with several thousand members, and the Stern Gang (Freedom Fighters of Israel) with several hundred. The Hagana, as the oldest of the groups, dated back to the nineteenth century. It had functioned as a Jewish police and military force since World War l. All three groups had been importing and manufacturing arms before the war, but the war gave all of them opportunity to increase their strength both quantitatively and qualitatively. The Zionists had at least two new grievances to which they were ready to give some military expression. The first was the 1939 limitation on immigration, and the second was the curb on land transfers promulgated in 1940. The 1939 White Paper had actually allowed the immigration of 75,000 additional Jews over a five-year period, meaning 15,000 a year. After 1944 the Arabs were to determine the number of Jewish immigrants to be allowed, if any. The Zionists, however, were not prepared to accept the immediate reduction and a possible long-term stoppage of immigration, and they prepared to defy the British regulation and the Arab veto by bringing Jewish immigrants in illegally, Economic conditions and security needs being what they were. The British could not allow unauthorized admission. Already in 1940 three passenger steamships with 3554 illegal immigrants on board were intercepted off the Palestine coast. The Zionists also found the new land regulations unacceptable. The 1939 White Paper had already explained that further transfer of Arab land to Jews would have to cease because of the natural growth of the Arab population and because too much land had already been transferred to the Jews. Too great a landless Arab population had already been created and the existing standard of life for Arab cultivators was already too much threatened. Controls were needed, and these came a year later.In 1940 Land Transfer Regulations divided Palestine into three zones. In each of these different rules were applied. There was complete prohibition of land transfer in the hilly country and the south of Palestine; and no restrictions at all in certain parts of the coastal plain and the area around Jerusalem. In other areas, including such fertile valleys as Esdraelon and such barren areas as Negev, particular land purchases by Jews required the approval of the Palestine government. Through the Muslim Supreme Council the Arabs approved the regulations, while the Zionists vigorously opposed them, in spite of the fact that in the first year land purchases proceeded at a level only slightly lower than the average for the previous years. The Zionists claimed, as so often before, that restrictions such as the 1940 regulations were against the Mandate and that tile Arabs really were the real benefactors of Jewish expansion. They pointed out that the improvements already carried out in Arab farming were largely achieved by cultivators who had freed themselves of debt by selling some land and using the balance to improve themselves on the acreage remaining. In any event, the apparent turnabout in policy by the British in 1939-40 had the effect of putting the Jews on the offensive. Guerrilla operations, which had been felt already before 1939, now increased on a noticeable scale. Before the year had passed, the British had discovered a hoard of arms and ammunition in one of the settlements and over eighty Jews were arrested for transporting arms and bombs and otherwise engaging in military maneuvers. In 1942 tile Stern Gang came into prominence with a series of murders and robberies, apparently politically motivated, in the Tel Aviv area. In 1943 Hagana was involved in a widespread theft of arms from British forces in the Middle East. During 1944 Irgun Zvei Leumi was responsible for the destruction of much government property. Official Jewish spokesmen condemned the outrages perpetrated by Irgun as well as Stern Gang but otherwise did nothing to reduce them. The assassination in Cairo of Lord Moyne, British Minister of State for the Middle East, by Stern could not be undone, and the attempt to assassinate the British High Commissioner outside Jerusalem also had not been prevented. While the British were trying to curb and control Zionism and give preferential treatment to the Arabs, new support for Zionism was emerging in the United States. As a result of the war, Zionist headquarters had been transferred from London to New York with the effect that both Jews and Americans in general were affected by the Zionist program. These in turn were to have a profound effect on post-war solutions proposed for the Jewish refugee problem and the Palestine problem. Until the war, the feelings of American Jews on Zionism were ambivalent. Historical studies dating back to 1869 revealed that many American rabbis and scholars were opposed to Zionism on the grounds that Jews were "no longer a nation but a religious community.” Similarly, the American Jewish Committee, declaring its opposition to the Balfour Declaration in 1918, said: "The Committee regards it as axiomatic that the Jews of the United States have been established in it permanent home for themselves and their children.";' American Jews had very good reasons for opposing Zionism, explained Julius Kohan, a Jew who for twenty-six years had been a representative in the United States Congress from the State of California. Zionism, he said, created a divided allegiance to two countries and two flags. Moreover, Zionism as a doctrine was in conflict with free institutions. Besides, Palestine could never support the millions of Jews supposedly in danger of persecution. The United States government also had been quite cautious until the early 1940s, in spite of some earlier action supporting the Balfour Declaration. Throughout the twenties and thirties, the United States regarded the Middle East as belonging to the British political and military sphere, even though American missionary-educational-philanthropic enterprises in the Middle East dated as far back as: 1819. Economically, however, there were some involvements in the early 1900s, and the determination to tap Middle East oil seems to have been decisive in involving the United States further. Eventually, American oil companies invested some $2.85 billion in the Middle East, which brought a net annual influx of two billion dollars into the United States. The growth of Zionism in America helped to give a front-line place for Palestine on the American agenda. In 1942 - Zionists now numbered 200,000 -the international Zionist Congress was held in New York at the Biltmore Hotel. Its headquarters was transferred from London to New York, and the Congress advanced what became known as the Biltmore Program, defining Zionist aims as follows: The immediate establishment in Palestine of a Jewish Com-monwealth. The rejection of the British White Paper of1939. Unrestricted Jewish immigration to Palestine andsettlement in it. Control of immigration and settlement by the Jewish Agency. Formation and recognition of a Jewishmilitary force fighting under its own flag. Impressive fund-raising campaigns were initiated to help implement this program. Already from 1927 to 1942 American Zionists had raised 13 million dollars, at least half of all the money raised for developments in Palestine by world Jewry. Those amounts were only a fraction of what was to follow. Besides direct financial aid, American Jews contributed executive and engineering personnel to help develop industry and commerce in Palestine. Hundreds of Jews from America, some of them permanent immigrants, were engaged as builders, storekeepers, brokers, and in a variety of other business pursuits in the crossroads country. After the Biltmore Conference, the Zionist Organization of the United States pressed at all possible levels for the fulfillment of the announced program. The plight of the Jews in Europe, which now had become international knowledge, was used as a basis for appeals in both governmental and nongovernmental circles. Although the full extent of Jewish persecution in Europe and the extermination policies of the Nazis were not to be revealed until after the war, enough was known to cause considerable alarm in the West. Later the world learned that about six million Jews or 63.2 percent of European Jewry had died as a result of the war and Nazi occupation policies in twenty countries. The eastern European countries had suffered the heaviest losses (see Table 10).  In the United States and in Great Britain, there was increased agitation for the opening of immigration doors for the Jews. Strangely enough, the doors to be opened were not in the United Kingdom and in the United States but in Palestine. Already in January 1944 the United States Congress ex-pressed itself in favor of unrestricted immigration to Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish state. A more liberal immigration policy for the United States, however, was turned down by Congress, in spite of the repeated appeals by Presidents Roosevelt and Truman. The British Labour Party, taking a cue from the action in the United States, passed a resolution suggesting that efforts be made to encourage the Arabs to move out of Palestine and make room for the Jews. Some sectors of the Hebrew press denounced such a strong resolution and expressed the hope that Zionist aims could be achieved without displacing or harming the Arab population. The 1944 Labour Party resolution, however, reflected the direction of Labour government policy following its election to power in 1945. Encouraged by Labour sentiments, the World Zionist Conference, meeting in London in August, 1945, endorsed the petition regarding the Jewish homeland which the Jewish Agency in Palestine was presenting to the British government. The petition included the following requests: l. That a decision to establish Palestine as a Jewish Statebe announced immediately. 2. That the Jewish Agency be invested with all necessary authority to bring to Palestine as many Jews as may be found necessary and possible to settle, and to develop, fully and speedily, all the resources of the country, es-pecially land and power resources. 3. That an international loan and other help be given for the transfer of the first million Jews to Palestine, and for the economic development of the Country. 4. That reparations in kind from Germany be granted to the Jewish people for the rebuilding of Palestine, and, as a first installment, that all German Property in Palestine be used for the resettlement of Jews from Europe. 5. That international facilities be provided for the exist and transit of all Jews who wish to settle in Palestine. The overtures being made to the new British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, by the Zionist Congress were at the same time being reinforced by messages from President Truman, who was encouraging Attlee to admit 100,000 Jews to Palestine to alleviate the situation in Europe. Truman, it must be said, was much more susceptible to Zionist pressures than Roosevelt had been. Just two months before his death the latter had assured the King of Saudi Arabia that he would make no move hostile to the Arab people. In the meantime, the Arabs had also been encouraged in their nationalism and pan-Arabism by the British and to a lesser degree by the United States. Both were recognizing increasingly the importance of Middle East oil deposits to the industrial growth of the West. Thus, while the Jews were being encouraged to make Palestine their home, the Arabs were being advised to unify, to modernize, and to remain in close relation with the West. The British, remembering their pledge to Hussein in 1916 regarding the establishment of an Arab state or a confederation of states, encouraged the Arabs to move in the direction of complete independence. The Arab leaders did not have to be prodded. Egypt, Iraq, Transjordan, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen already had measures of independence, although all stood in some relationship to Great Britain. The next step necessary was to secure also the independence of Syria and Lebanon from the French, and this was accomplished in 1941. The consolidation of pan-Arabism was achieved after two years of negotiations and the formation of the Arab League in Cairo in March of 1945. External unity might have been achieved somewhat earlier if the rivalries within the Arab world would not have prevented disagreement on Palestine. That Palestine should be an Arab state was assumed, of course, but with which of the Arab power blocks the state would be allied was another question. Abdullah of Transjordan saw Palestine and Transjordan as a nucleus of the Kingdom of Greater Syria to be ruled by the Hashemites. Iraq, on the other hand, saw Arab unity only in terms of a Greater Syria under an Iraqi hegemony, which would exclude Egypt or Saudi Arabian influence. Saudi Arabia was reluctant to accept any situation that would give addi-tional influence either to Iraq or Transjordan. And Egypt was likewise reluctant to accept any growth of power east of the Suez that was not Egyptian in orientation. Eventually, however, the members of the Arab League agreed sufficiently to include some paragraphs on policy regarding Palestine in the pact signed in Cairo. The policy recognized the Arab Higher Committee of Palestine as a voting member of the League and gave its position on Palestine as follows: At the termination of the last great war, the Arab countrieswere detached from the Ottoman empire. These included Palestine, vilayat of that empire, which became autonomous, depending on no other power. The Treaty of Lausanne pro-claimed that the question of Palestine was the concern of the interested parties, and although she was not in a position to direct her own affairs, the covenant of the League of Nations in 1919 settled her regime on the basis of the acknowledgement of her independence. Her international existence and independence are therefore a matter of no doubt from the legal point of view, just as there is no doubt about the independence of the other Arab countries. Although the external aspects of that independence are not apparent owing to force of circumstance, this should not stand in the way of her participation in the work of the council of the League." Meanwhile, the British government under Mr. Attlee was not immediately prepared to follow the suggestion of President Truman that 100,000 immigrant certificates be granted to displaced European Jews for resettlement in Palestine. His Majesty's government, therefore, sought the agreement of the United States to the appointment of an Anglo-American Com-mittee of Inquiry to examine the political and social conditions in Palestine as they related to the problem of Jewish immigration and settlement, the position of Jews in the European countries and the opinions of leading Arabs and Jews. The committee of twelve members had a time limit of 120 days and began its work in Washington on January 4, 1946. Its unanimous report was signed at Lausanne on April 20 and recommended that the future of Palestine should be based -on three principles: 1) that Jews should not dominate Arabs and that Arabs should not dominate Jews in Palestine; 2) That Palestine should be neither a Jewish state nor an Arab state; 3) That the form of government ultimately established should under international guarantees fully protect and preserve the -interests of the Christian. Muslim and Jewish faiths in Palestine as a "Holy Land." Partition of the land, as had been recommended in 1937 as a solution to the Palestine problem, was rejected outright by the committee, since such a measure would only lead to civil strife. The continuation of the Mandate was recommended until such a time as self-governing institutions could be established. To this the Arabs agreed. Then, however, the Anglo-American Committee endorsed practical measures that the Arabs knew militated against the theoretical position that the Jews should not achieve a dominant position. It was recom-mended, for instance, that the land-transfer regulations of 1940 be revoked and that the Mandate government authorize 100,000 immigration certificates immediately. President Truman was delighted with the report of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry. He expressed pleasure that 100,000 Jews would be admitted to Palestine immediately and that the demands of the White Paper of 1939 had actually been rescinded by the report. The Prime Minister of Great Britain was not quite that enthusiastic. He insisted that the illegal military formations in Palestine be disarmed as a pre-condition for the admission of 100,000 Immigrants. The report was now given to further examination by British add American officials. Meeting in London during June and July, they came to the conclusion that Palestine should not be partitioned, but rather divided into two provinces, one Arab and one Jewish, with a central government administered by the British High Commissioner. The central government would have exclusive authority in matters of defense, foreign relations, customs and excise, and initially also in domestic law and order. The provinces would have a legislature and an executive, and a wide range of functions including control over land regulations and immigration. The Jewish province should be the entire area on which Jews have already settled, together with a considerable area between and around these settlements. This arrangement assumed that the Arab province would have full power to exclude all the Jewish immigrants, while the Jewish province would be able to admit as many immigrants as it’s government desired. These conditions should make possible the immediate admission of 100,000 Jewish immigrants into Palestine and continued immigration thereafter. On July 25, 1946, His Majesty's government approved in principle the policy recommended by this group of British and American officials as a basis for negotiation with both the Arabs and the Jews. The Arab League, meeting in Syria to consider the report of the Anglo-American Committee, was not enthusiastic about the Committee's conclusions. On the contrary, the League asked the British government to decide the Palestine issue in conformity with the United Nations Charter. The Arab states were assuming, and not incorrectly, that the Charter, with its emphasis on the self-determination of peoples, was in their favor. Consequently, they suggested the calling of a conference to prepare an Arab proposal for the fall session of the United Nations General Assembly. The United Nations was in 1946 only one year old. A by-product of World War II, the UN was determined to be an effective instrument of international peace and security and to save mankind from the scourge of war. In doing so, the UN resolved to respect, and promote respect for, human rights and fundamental freedoms. However, it was still young and weak, and the victorious powers of World War II, in-cluding Britain and the United States, continued to act in-dependently of it in a number of questions, including Palestine. Since the British government had at various times given pledges to consult the interested parties before reaching a decision on Palestine, the idea of a conference was accepted, and the London Conference of 1946-47 came into being on September 9. However, only the representatives of the in-dependent Arab states and the Secretary-General of the Arab League attended. Neither the Jews nor the Palestinian Arabs accepted the invitation. The Arab delegates soon made it known that they were in complete opposition to the provinces plan for Palestine. Asked to present their alternative, they outlined a proposal that contained the following main features: 1. Palestine should be a unitary state with a permanent majority of Arabs. Independence would -come after a short period of transition (two or three years) under the British Mandate. 2. Within this unitary state, Jews who had acquired Palestinian citizenship (for which the qualification would be10 years residence in the country) should have full civilrights and equality with all other citizens of Palestine. 3. Special safeguards should be provided to protect the religious and cultural rights of the Jewish community. 4. The sanctity of the holy places should be guaranteed and safeguards provided for freedom of religious practice throughout Palestine. 5. The Jewish community should be entitled to a number of seats in the legislative assembly proportionate to the number of Jewish citizens in Palestine, subject to the provision that in no case would the number of Jewish representatives exceed one-third of the total number of members. 6. All legislation concerning immigration and the transfer of land should require the consent of the Arabs in Pales-tine as expressed by a majority of the Arab members of the legislative assembly. 7. The guarantees concerning the holy places should be al-terable only with the consent of the United Nations; and the safeguards provided for the Jewish community would be alterable only with the consent of a majority of the Jewish members of the legislative assembly. The representatives of the Arab states wanted the new government to come into being immediately. The first step would be to establish a provisional government consisting of seven Arabs and three Jews by nomination of the High Commissioner. This government in turn would then arrange for the election of a constituent assembly, and the assembly in turn would within six months draw up a detailed constitution with the above general principles in mind. Should the assembly fail in its task within the prescribed time, the provisional government would itself promulgate a constitution, and the scheme could then proceed to be implemented even in the face of a Jewish boycott. After the adoption of a constitution, a legislative assembly would be elected and the first head of the independent Palestine state would be appointed, receiving his authority immediately from the High Commissioner. The London Conference was suspended to allow certainrepresentatives to attend the Assembly of the United Nations.During this recess the Zionist Congress met in Basel. ThisCongress was violently opposed to the provincial autonomyplan because it would deny settlement in other parts of Palestine and deny complete autonomy even in the territory al-located to the Jews. The Congress also expressed opposition to a United Nations trusteeship taking the place of the Mandate. As far as the Zionists were concerned, a further delay in establishing a Jewish state was totally unacceptable. Unless there was some immediate movement in that direction, the Zionists could not, they said, take part in the London Conference. Their own political aims were expressed in the following terms: 1. The establishment of Palestine as a Jewish commonwealthintegrated into the structure of the democratic world. 2. The opening of the gates of Palestine to unrestricted Jewish immigration. 3. The control of immigration into Palestine to rest in the hands of the Jewish Agency, which agency should also have the necessary authority for the upbuilding of the country. The Anglo-Arab Conference resumed its work in January 1947, and this time a parallel Anglo-Jewish Conference was held simultaneously. The British, recognizing how far apart the Arab and Jewish positions were, made the suggestion that the British trusteeship be extended five more years in order to prepare the country for independence, granting a considerable amount of local autonomy during this period. Within four years a constituent assembly would be elected and, if a majority of Arab representatives and a majority of Jewish representatives could reach agreement, an independent state would be established immediately. If agreement could not be reached, the trusteeship council of the United Nations would advise on future procedure. Since the welfare of Palestine as a whole had to be taken into consideration, Jewish immigration could not be unlimited and only 96,000 should be admitted in the first two years o' the trusteeship agreement. These British proposals, however, were not well received. Both the Jewish Agency and the Arab delegation, which now also included a representative of the Palestine Arab Higher Executive, rejected them. In the meantime, Zionist guerrilla activities, acts of terrorism, and sabotage had increased dramatically. An average of two British policemen or soldiers were being killed every day. The targets of the attacks included the central prison in Jerusalem, a coast guard station, the radar station on Mount Carmel, police installations, air fields, and railway lines. Jewish forces also saw to it that illegal immigrants now arriving in large numbers (see Table 11) disembarked successfully.  The peak of terrorism came on July 22, 1946 when a wingof the King David Hotel in Jerusalem was blown up byJewish terrorists. The Hotel housed the British secretariat andpart of the military headquarters, and in the explosion 83public servants and five other civilians were killed. Two dayslater the British issued a White Paper on terrorism in Palestine, in which the following main conclusions were recorded: 1. The Hagana and its associated forces working under the political control of prominent members of the Jewish Agency have been engaged in carefully planned use of violence and sabotage under the name of the Jewish resistance movement. 2. The national military organization and the Stern Group had during the preceding eight or nine months been cooperating with the Hagana in certain of these operations. 3. The illegal radio transmitter calling itself the Voice of Israel, working under the general direction of the Jewish Agency, had been supporting the terrorist groups. Terrorism continued in spite of the accusations. and in February the demolition of an officers' club in Jerusalem cost the lives of 20 persons, including military police and civilians. At one settlement, a week's search uncovered 33 caches of weapons, including 10 machine guns, 325 rifles, 96 mortars, 5,267 mortar bombs, 5,017 grenades, 800 pounds of explosives, and 425,000 rounds of small arms and ammunition. On February 18, 1947, shortly after the failure of the London Conference, the foreign secretary made a speech in the British House of Commons admitting that His Majesty's gov-ernment was faced with an irreconcilable conflict between1,200,000 Arabs and 600,000 Jews now in Palestine and that the Mandate had proven itself to be unworkable. The foreign secretary said, in part: We have, therefore, reached the conclusion that the only course now open to us is to submit the problem to the judgement of the United Nations. We intend to place before them an historical account of the way m which His Majesty's government has discharged their trust in Palestine over the last 25 years. We shall explain that the Mandate has proven to be unworkable in practice, and that the obligations undertaken to the two communities in Palestine have been shown to be irreconcilable. We shall describe the various proposals which have been put forward for dealing with the situation, namely, the Arab plan, the Zionist aspirations, so far as we have been able to ascertain them, the proposals of the Anglo-American Committee and the various proposals, which we ourselves have put forward. We shall then ask the United Nations to consider our report, and to recommend the settlement of the problem. We do not intend ourselves to recommend any particular solution. The British admission was a signal to the Zionists that they might be in reach of their goal of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. Terrorism and sabotage thus increased dramatically, as did the arrival of illegal immigrants. In March alone nearly five thousand illegal immigrants arrived, and this rate was continued in succeeding months. No sooner had the British made their announcement in the House of Commons when the Council of the Arab League met for the seventh time in Cairo, again to discuss the Palestine question. The League declared that the question might very well go to the United Nations but that it should be discussed only on the basis of Palestine's becoming an independent country. More financial support was also given to the Arab Higher Committee, and the League threatened to review Arab economic relations with Great Britain and the United States if these countries would not promote the independence of Palestine on democratic grounds. When the specially called session of the United Nations General Assembly opened on April 28, the Arab govern-ments of Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia requested the inclusion of all additional item on the agenda. At that point tile agenda included only the British request, namely, "the termination of the mandate over Palestine and the declaration of its independence." The reasons for this re-quest, the Arab governments said, was that the problem before the General Assembly was not the finding of more facts but the establishment and application of certain principles, such as those espoused in the Covenant of the League and the Charter of the United Nations. These principles, said the League, were inconsistent with the Palestine Mandate and with the Balfour Declaration, which were based on expediency, power politics, local interests,and local pressures. The Arabs also insisted that the problem of the Jews-there were still many Jewish refugees and displaced persons in European camps -was a separate problem from that of Palestine. The United Nations, however, did not see fit to put the Arab request on the agenda. The proposal was soundly defeated, with 15 members in favor, 24 opposed, and 10 abstaining. Instead, the United Nations Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) was established to study the whole future of Palestine. The committee included representatives from Australia, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, India, Iran, the Netherlands, Peru, Sweden, Uruguay, and Yugoslavia. In mid-June [JNSCOP arrived in Palestine and conducted 36 meetings as an integral part of its inquiry. The Arab Higher Committee had cabled the United Nations' Secretary General that they would not cooperate with the Committee, since it felt that UNSCOP was predisposed toward accepting a Zionist solution. The Arab Higher Committee also made it clear that it was not opposed to giving due consideration to world religious interests; however, these were a separate question from the status of Palestine. Tile natural rights of the people of Palestine were self-evident on the basis of the principles of the United Nations Charter and need not be subject to another investigation. Again the Committee asked that tile issues of Palestine and of the Jewish refugees be separated. In the minds of the Jews, however, Palestine and the Jewish refugee problem were intimately interwoven. After visiting the refugee camps of Europe, UNSCOP reported seeing posters stating "Palestine - a Jewish State of Jewish People." Large pictorial designs in the camps showed Jews from eastern Europe marching toward Palestine, which was shown in a much larger area than the geographical limits of the Mandate. Children in the various camp schools were being taught detailed historical and geographical knowledge of Palestine. The UNSCOP report submitted on August 31, 1947 included two proposals. The majority proposal, supported by Canada, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, the Netherlands, Peru,Sweden and Uruguay, was a plan of partition with economic union. Palestine should be divided into an Arab state, a Jewish state, and the city of Jerusalem, which was to be placed under an international trusteeship administered by the United Nations. The Arab and Jewish states should become independent after a transitional period of two years beginning September 1, 1947, during which time the United Kingdom would pro-gressively transfer the administration of Palestine to the United Nations. The constitutions of the respective states should con-tain provisions for the preservation of and free access to all the holy places. During the transitional period and for three years, Jewish immigration into Palestine would be permitted, depending upon the absorptive capacity of the country. Such capacity should be determined by an international commission set up for the period of three years and composed of three Arabs, three Jews, and three United Nations representatives. The minority proposal, supported by India, Iran, and Yugo-slavia, included a plan for a federal state that would comprise an Arab state and a Jewish state, with Jerusalem as its capital. The federal state would have full authority with regard to national defense, foreign relations, immigration, currency, taxation for federal purposes, foreign and interstate waterways, transport and communications, copyrights and patents. The Arab and Jewish states would enjoy full powers of local self-government and would have authority over education, taxation for local purposes, the right of residence, commercial licenses, land permits, grazing rights, interstate migration, settlement, police, punishment of crime, social institutions and services, public housing, public health, local roads, agriculture and local industries. The UNSCOP report was submitted to an ad hoc committee on the Palestine question, who debated it vigorously from October 4-16. During the debate, seventeen proposals were submitted to the committee including those of' the Jewish Agency and the Arab states. The Zionists were enthusiastic about the majority plan be-cause it fully :accorded with their aspirations for a Jewish state, even though they would like to have seen this state larger than recommended by the partition plan. However, they were prepared to accept it as "the indispensable minimum." The rest would come later. The Arab governments rejected both the majority and minority plans outright, because in their opinion they both violated the Charter of the United Nations and the demo-cratic right of a people to self-determination. They declared that they were in favor of an "independent unitary state embracing all of Palestine in which the rights of the minority would be scrupulously guarded." Supported by the World Zionist Organization, the Jewish Agency was most aggressive in promoting its point of view and supplied the United Nations and its members with volumes of documentation to support its claims for the establishment of a Jewish state in the whole of Palestine. The Jewish appeals were based on what was called "the agony of the Jews" in Europe, as well as the plight of Jews in Muslim lands, the Balfour Declaration, the League of Nations Mandate and the findings of the Anglo-American Palestine Committee. The Agency also submitted that the land of Palestine could support many thousands, if not millions of people, and that the potential for Jewish mass immigration into Palestine was very large. Besides, Palestine would contribute to the welfare of the entire Arab world. The economic achievements of the Jews in Palestine to date, which were considerable, were presented as evidence of the capacity of both Palestine and the Jews. On the land already under cultivation, Palestine could easily settle 2,800,000 persons, and the water resources were such that millions of additional dunams could be irrigated to support additional thousands. So said the Agency. Much sympathy for the Zionist cause was now apparent in America. The plight of the Jews in Europe now resulted in an attempt to redress earlier wrongs occasioned by European anti-Semitism. The American conscience wanted to do right by the Jews, as the British had done in the previous century by promising a homeland to the Jews. Just as British Christianity provided support for English interests in Palestine and the Middle East in the nineteenth century, so American Chris-tianity now became the ideological and emotional wellspring of support for the Middle East aspirations of America in general and of Zionism in particular. Most of the Christian support for Jews and Zionism and much of the Zionist message to Christians were channeled through the American Christian Palestine Committee (ACPC). The exploitation of Christian sympathy for the Zionist cause had begun immediately after the extraordinary Zionist con-ference in New York's Biltmore Hotel in 1942. Field workers were dispatched across the nation to build local chapters of what was then known as the American Palestine Committee, the forerunner of the ACPC. By 1948 the American Zionist Emergency Council was spending up to $150,000 annually for work among non-Jews, meaning Christians, and local Zionist Organizations of America chapters were exhorted to provide their Christian Zionist neighbors with funds, clerical services, and moral support. The goal was "to crystallize the sympathy of Christian America for our cause, That it may be of service as the opportunity arises." Christians by the tens of thousands rallied to the support of the American Christian Palestine Committee, believing that the destiny of the Jews was of immediate and urgent concern to the Christian conscience. The Zionists reminded the Christians that the Old Testament supported the return of present day Jews from their exile to their national home in Palestine. It was not difficult to convince many that the cause of Zionism was scriptural, because hundreds of Christian teachers and preachers were associating Christian fulfillment with the: return of the Jews to Palestine. The increase of ideological and emotional support for the Zionist cause made it relatively easy for the Zionists to translate empathy into favorable public opinion and political support, and American decisions in turn affected the positions of other nation states. President Truman later admitted the pressure of the Zionist leaders, and in his memoirs he said: I do not think I have ever had as much pressure and propaganda aimed at the White House as I had in this instance. The persistence of a few of the extreme Zionist leaders - actuated by political motives and engaging in political threats -disturbed me and annoyed me. Individuals and groups asked me usually in rather quarrelsome and emotional ways, to stop the Arabs, to keep the British from supporting the Arabs, to furnish American soldiers, to do this, that, and the other. The President was opposed in his leanings toward the Zionist cause by a number of close colleagues, including Secretary of State Dean Acheson, who did not believe that Palestine was a solution to the Jewish refugee problem nor that America's best interests would be represented by following the Zionist line. In his memoirs he explained his position as follows: ... The number that could be absorbed by Arab Palestine without creating a grave political problem would be inadequate, and to transform the country into a Jewish state capable of receiving u million or more immigrants would vastly exacerbate the political problem and imperil not only America but all Western interests in the Near East. From Justice Brandeis, whom I revered, and from Felix Frankfurter, my intimate friend, I had learned to understand, but not to share, the mystical emotion of the Jews to return to Palestine and end the Diaspora. In urging Zionism as an American government policy they had allowed, so I thought, their emotion to obscure the totality of American interests. In spite of the opposition, President Truman was "sucked in," to use Acheson's words, and thereafter he himself exertedpressure on members of the United Nations or had such pressure exerted in his, name. Secretary of Defense James Forrestal claimed in his diary that the methods used to get votes in the General Assembly "bordered closely on to scandal"; and Sumner Welles, a former Undersecretary of State, wrote: By direct order from the White House, every form of pressure direct or indirect was brought to bear by American officials upon those countries outside the Muslim world that were known to be either uncertain or opposed to partition. Representatives of intermediaries were employed by the White House to make sure that the necessary majority would at length be secured. Other Jewish leaders, however, were deeply troubled by the Zionist program both before and after the UN decision. A conference of American rabbis had announced, in what became known as the Pittsburgh Platform, that Jews were "a religious community" and not a nation. The American Council of Judaism likewise vigorously opposed the establishment of "a national Jewish state in Palestine or anywhere else" and dissented "from all these related doctrines that stress the racialism, the nationalism, and the theoretical homelessness of Jews," Others, like Rabbi Isserman, expressed the belief that political Zionism was "a liability to prophetic religion" and that the return of the Jews to Palestine as a fulfillment of prophecy was not a Jewish but a Protestant idea. The Jewish biochemist I. M. Rabinowitch foresaw that "a Jewish state in Palestine meant war" and that the alleged sanctuary for Jews "could readily become a death trap." Others like Morris Cohen identified Zionism with tribalism, while men like Yehezkel Kaufmann saw in political Zionism "the ruin of' the soul." Some Jewish leaders clearly saw how unacceptable and unadaptable a Jewish state must be to the Arab world. New York Times publisher A. H. Sulzberger expressed the belief that Arabs could easily accept as many as 350,000 Jewish refugees but that they could never make room for a Jewish state. Jabir Shibli explained the Arab viewpoint that a Jewish state would be a misfit in the Middle East thus: Palestine is the heart and center of the Arab world, extending as it does from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean. Palestine is the keynote state of the coming Arab union. Its settlement by Jews would be equivalent to the occupation of Pennsylvania by France or Russia. Palestine is the only bridge between the 20 million Arabs of western Asia and the 40 million Arabs of northern Africa. Its conversion into a Jewish state would sever the Arab world and prevent its unification. It is no wonder that the Arabs are determined at any cost to keep Palestine in the Arab fold. All of these warnings, however, did not discourage Zionistsin America or in Palestine, and the Zionist movement ad-vanced, to use the words of Rabbi Miller Berger, "like the march of a ruthless Goliath."While the Zionists were presenting their case inside and outside the United Nations directly and indirectly, the Arabs too were making a last attempt to impress the world community with their position. Strangely enough, they did not exploit the economic power represented by their petroleum resources to obtain their objectives, and in the end they lost out. When the president of the General Assembly in the United Nations called for a vote on the recommendations of the ad hoc committee on November 29, 1947, the result was 33 in favor of the majority partition plan with economic union, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The two-thirds majority was obtained only by some remarkable lobbying. At the last moment eight doubtful members were persuaded by the partition lobby. The eastern European Communist countries at this point were very much sympathetic to the Jews, because it was in eastern Europe where so many had died at the hands of the Nazis. One newspaper correspondent commented: The general feeling among the delegates was that regardlessof its merits and demerits and tile joint support given by the USSR and the USA the partition scheme would have been carried in no other city than New York.... The strength of tile Jewish influence in Washington had been a revelation. Those who voted in favor of partition were Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil. Byelorussian SSR, Canada, Costa Rica, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, France, Guatemala, Haiti, Iceland, Liberia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua. Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Sweden, Ukrainian SSR, Union of South Africa, USSR, United States of America, Uruguay and Venezuela. Voting against were Afghanistan, Cuba, Egypt. Greece. India, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey and Yemen. Those who abstained included Argentina, Chile, China, Colombia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Honduras, Mexico, United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia. After the partition resolution had been passed, the Jewish Agency for Palestine indicated its acceptance, while the Arab Higher Committee and the Arab delegates from Arab countries said that they would oppose the implementation of the partition plan. Their reasons were those given many times before. They believed that the plan would be unworkable and that it would bring perpetual war to the area. They also believed that the United Nations had no jurisdiction to partition countries and that the action was illegal. undemocratic, and contrary to the principle of self-determination contained in the Charter. The Arabs also objected to the nature of the partition itself. The partition resolution allotted the proposed Jewish state 56 percent of the total area of Palestine at a time when Jewish ownership of land did not exceed six percent of the total area of the country and only nine percent of the area of the proposed Jewish state (see Map 9). Besides, the Jewish portion of the land, except for the Negev desert, was better than the Arab portion, which consisted largely of arid and mountainous regions with little irrigation possibilities and very sparse cultivable areas. Perhaps the greatest objection lay in the fact that the Jewish state would include within its territories as a permanent minority almost as many Arabs as Jews   According to the partition resolution passed by the United Nations General Assembly, the independent Arab and Jewish states and the special international regime for the city of Jerusalem (see Map 10) should come into effect two months after the evacuation of the armed forces of the Mandatory power, but in any case not later than October 1, 1948. The British set August 1 as the date for their final withdrawal of Mandatory power. With that announcement, both- the Jews and Arabs determined that their cause would win, and in the ensuing contest the Jews pressed their claim most forcefully and most successfully. Thirty years of struggle tinder the British Mandate, fifteen years of heartache over the plight of Jewry, in Hitler's Europe, and two thousand years of longing for a homeland had ended. Civilization ... had invested Me Jewish people n0t/r nationhood. -Frank Gervasil The last remaining legal obstacle to the creation of a national Jewish state had been removed by the United Nations Partition Resolution, but there were other problems to be over-come. Foremost of these was the unwillingness of the Palestinian Arabs and the Arab states to recognize this international authorization of a new state. As they saw it, the legalization of Israel meant dehumanization for the Arabs. Thus it happened that the United Nations, far from solving a problem, created a situation that resulted in three major wars in twenty years, none of which solved the problem. Jews throughout the world hailed the United Nations decision with joy, and there was dancing in the streets of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, but there was also a strong awareness that many problems lay ahead. Chaim Weizmann, who later became the first president of Israel, recognized that Arabs would not easily accept the loss of their political independence, but he expressed the belief that they would feel themselves "largely compensated for by what they gain in other respects." Other Jews like Ben-Gurion, the first Prime Minister of Israel, promised that Arabs and other non-Jewish neighbors would be treated on "the basis of absolute equality as if they are Jews," but then he added a disclaimer reminiscent of earlier British vacillation between the two viewpoints:When we say Jewish independence or a Jewish state, we meanJewish country, a Jewish soil, Jewish labor, we mean Jewish economy, Jewish industry. Jewish sea. We mean Jewish language schools, culture; we mean Jewish safety, security, independence. complete independence as for any other people. In Palestine itself specific preparation for the establishment of the Jewish state had been in progress even while the UN was still debating the Palestine question. The Jewish com-munity had for years already been organized into a quasi--government with its own health, educational, social, and military defense services. An Elected Assembly, a quasi-parlia-ment, had been functioning for some time, and its cabinet, the National Council of Executives, was together with the Jewish Agency administering those aspects of communal organization not attended to by the British. The administration was efficient, because "within the Jew-ish community there was a large body of individuals trained and experienced in European government, the mandatory of-fices, and the Jewish national institutions." Given the Zionist goal and the human resources to engineer its achievement, it is not too surprising that the Agency and the Executives were ready for the UN decision. Plans had been drawn up for the maintenance of essential government services after the departure of the British. Plans had been laid for a constitution and a le-al code for the new Jewish state. As the UN announced its decision, the Elected Assembly decreed the total mobilization of Jewish manpower. Hagana was converted into a regular army; and all possible efforts, both legal and illegal, were now made to increase Jewish immigration, with special attention to the immigration of the young. Military preparedness was attended to in other ways as well, as Fred J. Khouri has observed: Jewish as well as non-Jewish veterans of Allied armies-pilots, engineers, naval experts, and the like -were hastily recruited. Arms and military equipment were desperately sought from various sources. New Jewish villages in strategic areas were hurriedly set up. The Palestinian Arabs, on the other hand, were much less equipped and ready for the end of the British administration. They had no quasi-government and few elected administrators. They had no experience in self-rule, though their national sentiment was strong. Thus their reaction was similar to what it had been in the past thirty years. While the Jews rejoiced on November 29, 1947, the Arabs demonstrated and started a gen-eral strike. Fighting broke out in Jerusalem. Haifa, Tel Aviv, and Jaffa, and this fighting spread. In two months (from December 1, 1947 to February 1, 1948) there were nearly three thousand casualties, the majority of them Arabs (1,462). The Jews had lost 1,106 and the British 181. The United Nations meanwhile was helpless to ameliorate the strife between the two communities. A decision to implement peace in Palestine had been made, but implementing it peacefully was quite another- matter. The Palestine Commission, which was set up to implement the resolution, could not get the Arab Higher Executive to cooperate at all, and the British were also less than enthusiastic about partitioning Palestine. Britain even announced that she would not share her power with the Commission. The British would leave Palestine on May 15 and the Commission could enter only two weeks before that. The result was that only one representative of the Commission entered Palestine; and there was very little he could do except to prepare a number of reports. The first special report of the Palestine Commission of February 24, 1948, advised the UN that the Arabs were and would be resisting the partition resolution by force and that no peaceful implementation was in sight. By that time the US State Department had also come to the conclusion that the partition plan was unworkable and that the US should take steps to have the partition proposal reconsidered.President Truman, however, was of a different mind. Or March 19 the US took the position that the UN might en-force a temporary trusteeship after the departure of the British; the Zionists, however, did not approve of that idea, and soon they were doing all in their power to block the trusteeship plan and threatening to use force to prevent trusteeship in the same way that the Arabs were threatening to use force to prevent partition. In Palestine itself military developments had already overtaken the political and diplomatic activities at the UN. Whenever it appeared that partition would be implemented, the Arabs resisted with attacks and raids on Jewish centers, and whenever it appeared that the UN was leaning toward the repeal of the partition resolution, the Zionist community intensified its military efforts to occupy as wide an area of the Holy Land as possible. The Zionists were operating on the assumption that "force of arms, not formal resolutions" would determine the issue, and that the fait accompli would finally be decisive. Accordingly, the war of independence as David Ben-Gurion called it, concentrated on gaining full control of various cities and Arab localities.'! At least 18 such attacks or occupations were reported by the New York Times between December 2, 1947 and May 8, 1948. The worst of these attacks was on April 9 when Irgun and Stern Gang soldiers entered Deir Yassin, a village, near Jerusalem, and massacred 250 men, women, and children. Such actions had the intended effect of panic among the Arabs, and by May 15, the date of the end of the British administration, some 200,000 Arab refugees had left Jewish occupied territory. The Jews, fresh from their terrifying European experience, also felt Arab pressure and believed once more that they were fighting for their survival. In Jerusalem the Arabs were cutting off water and food supplies to the 1,700 Jews in the Jewish quarter of the Old City and to the 100,000 Jews in the New City. Convoys of supplies were ambushed, and in one attempt to reinforce the Hadassah Medical Center on isolated Mount Scopus 77 men and women lost their lives, including a young scientist engaged to be married to David Ben-Gurion's youngest daughter. All of this, of course, strengthened Ben-Gurion's determination not to have independence postponed, and the Jews of Palestine found in him their Winston Churchill. He ordered every kibbutz, and settlement manned, fortified, supplied, and defended - Jerusalem was to be defended at any cost - and, as Gervasi has written, "suddenly no Jewish male was too old to fight or too young to die." By Ben-Gurion's own admission, however, the Arabs had acted with restraint: Until the British left, no Jewish settlement, however remote,was entered or seized by the Arabs, while the Haganah captured many Arab positions and liberated Tiberias and Haifa. Jaffa and Sated.... So, on the day of destiny, that part of Palestine where the Haganah could operate was almost clear of Arabs. The moment of destiny was midnight May 14, 1948, the time of the termination of the British Mandate. The UN Partition Resolution had decreed that partition should not go into effect until two months later, on July 15, assuming that the Palestine Commission had not yet become effectively functional. On May 14 the UN General Assembly met to vote on the plan to appoint a UN Mediator (the vote was 37 to 7 with 16 abstentions) to reexamine the situation and to promote a peaceful adjustment of the future situation of Palestine. The Zionists, however, presented the UN with the accom-plished fact. One hour before the: UN General Assembly convened, the Jewish Agency announced that the new State of Israel had been proclaimed. Shortly after the press was advised that President Truman had given full recognition to the new state sixteen minutes after the official proclamation in Tel Aviv. The "proclamation of independence" read in part: The Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people.... Exiled from the Land of Israel, the Jewish people remained faithful to it in all the countries of their dispersion, never ceasing to pray and hope for the return and the restoration of their national freedom.... In the year 1897, the First Zionist Congress, inspired by Theodore Herzl's vision of the Jewish State, proclaimed theright of the Jewish people to national revival in their own country. This right was acknowledged by the Balfour Declaration of November 2, 1917, and re-affirmed by the Mandate of the League of Nations.... The recent holocaust, which engulfed millions of Jews in Europe, proved anew the need to solve the problem of the homelessness and lack of independence of the Jewish people by means of the re-establishment of the Jewish State.... In the Second World War the Jewish people in Palestine made their full contribution to the struggle of freedom-loving nations against the Nazi evil.... On November 29, 1947, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted a Resolution requiring the establishment of a Jewish State in Palestine. It is the natural right of the Jewish people to lead, as do all other nations, an independent existence in its sovereign State. ACCORDINGLY WE, the members of the National Council, representing the Jewish people in Palestine, and the World Zionist Movement, are met together in solemn assembly today, the day of termination of the British Mandate for Palestine; and by virtue of the natural and historic right of the Jewish people and of the Resolution of the General Assembly of the United Nations. WE HEREBY PROCLAIM the establishment of the Jewish State in Palestine, to be called "Medinat Israel" (The State of Israel). WE HEREBY DECLARE that, as from the termination of the Mandate at midnight, the 14th- l5th May, 1948, and pending the setting up of the duly elected bodies of the State in accordance with a Constitution, to be drawn up by the Constituent Assembly not later than the 1st October; 1948, the National Council shall act as the Provisional State Council, and that the National Administration shall constitute the Provisional Government of the Jewish State, which shall be known as Israel. THE STATE OF ISRAEL will be open to the immigration of Jews from all countries of their dispersion; will promote the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; will be based on the principles of liberty, justice and peace as conceived by the Prophets of Israel; will uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race or sex: will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, education and culture; will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and will loyally uphold the principles of the United Nations Charter. THE STATE OF ISRAEL will be ready to cooperate with the organs and representatives of the United Nations in the implementation of the Resolution of the Assembly of November 29, 1947, and will take steps to bring about the Economic Union over. the whole of Palestine. We appeal to the United Nations to assist tile Jewish people in the building of its State and to admit Israel into tile family of nations. In the midst of wanton aggression, we yet call upon the Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel to preserve the ways of peace and play their part in the development of the State, on the basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its bodies and institutions- provisional and permanent. We extend our hand in peace and neighbourliness to all the neighbouring states and their peoples, and invite them to cooperate with the independent Jewish nation for the common good of all. The State of Israel is prepared to make its contribution to the progress of the Middle East as a whole. Our call goes out to the Jewish people all over tile world to rally to our side in the task of immigration and development and to stand by us in the great struggle for the fulfill-ment of the dream of generations for the redemption of Israel. With trust in Almighty God, we set our hand to this Declaration, at this Session of the Provisional State Council, on the soil of the Homeland, in the city of Tel Aviv, on this Sabbath eve, the fifth of Iyar, 5708, the fourteenth day of May, 1948. With the Israeli Proclamation of Independence, full-scale fighting broke out. The armed forces of the surrounding Arab governments moved into Palestine. Explaining the action to theUnited Nations Secretary-General tile Arab Lea-lie noted that until May 15 the British had been responsible for law and order, peace and security, and that whereas Zionist forces had already occupied such cities as Jaffa and Acre, assigned to the Arab state by the UN, they feared for the whole of the proposed Arab State of Palestine. The League also insisted that the unilateral proclamation of the State of Israel was juridically invalid for two reasons: 1) the majority (Arabs) rather than the minority (Jews) should determine by democratic vote the future of Palestine upon termination of the Mandate, and 2) the Jewish state was not, in any event, entitled to exist until two months after July 15. For the Jews, on the other hand, the action of the Arab governments was a threat to their very survival, even though they must have known that the armed forces of the Arab states were little prepared. Between them, the five nations most involved (Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Transjordan, Lebanon) had no more than 80,000 troops of varying qualities. Of these they dispatched at most 25,000 to assist the Palestinian Arab liberation forces. These forces, it might be added, included some 7,000 Arab volunteers from outside Palestine. All were poorly trained, poorly organized, and poorly led. The Provisional Government of the State of Israel, on the other hand, had a military manpower of some 60,000 in Hagana and several thousand in Irgun and Stern Gang, and all of these were integrated into a single armed force in June. While exceeding the Arabs in trained manpower resources, the Israelis lacked weapons. But on May 15, 30 shiploads of arms from Europe were on their way -some had already arrived - and some Jewish factories were quickly converted to military production. The Arabs lacked the engineering and industrial capacity of the Jews, and they also had the disadvantage of long lines of communication. The greatest strength of the Israelis, however, probably was their effective intelligence, their able leadership, and the high motivation of their entire population. In the end, the Palestine War of 1948 was to the Israeli advantage. Not only did they increase- their land area, but their armed forces and arms increased substantially.One week after inconclusive fighting, the United Nations Security Council adopted a resolution calling upon all govern-ments to cease their fighting, and a second more effective di-rective was issued another week later. Fighting was again resumed for nine days on July 9, but then the opposing parties accepted a cease-fire. The Swedish Count Folke Bernadotte was appointed mediator for the United Nations, but on September 17, 1948, before his task was completed, he was assassinated by men who wore the uniform of the Israeli army. The United Nations demanded that Israel bring the assassins to justice, but they could not be found. To the Arabs, Bernadotte remained a saint and a martyr because his report urged the immediate return of the Arab refugees to their homes. In November, the Security Council called upon the parties in the conflict to conclude an armistice, and one by one the Arab countries signed separate armistice agreements with Israel, as a result of which Israel came into control of about 8,000 square miles of territory, or 77.40 percent of the total land area of Palestine, instead of the 56.47 percent allotted to the Jewish state under the partition plan (see Map 11). The new territory included much of Galilee as well as new Jerusalem; the internationalization plan for that city having been defeated, they insisted that the conclusion of the armistice did not mean the recognition of Israel. A state of war, they said, still existed until a permanent settlement was reached. Each agreement included the proviso: It is also recognized that no provision of this Agreement shallin any way prejudice the rights, claims, and positions of either party hereto in the ultimate peaceful settlement of the Palestine question; the provisions of this Agreement being dikz1atwdexclusively by military, and not by political, considerations.  As the remaining part of Arab Palestine was annexed by Jordan, Israel established Jerusalem as her capital and applied for admission to the United Nations. The first application had been rejected in December 1948 because Israel had not fulfilled the requirements of the UN, meaning withdrawal from the territory assigned to the proposed Arab state and from the international zone of Jerusalem. On May 12, 1949, Israel was admitted, however, after signing the Lausanne Protocol of the UN Palestine Conciliation Commission. By that signing, Israel committed herself to observe the resolutions of the UN, specifically with respect to wrongly held territory and evicted refugees, of which there were over 700,000. These refugees represented three-fourths of the Arab population in Israeli-controlled territories. The victories -in the Palestine War gave the Israelis addi-tional incentives to develop their national community, which already had many of the attributes of a modern democratic state. The intense nationalism of pre-war years was many times strengthened. As soon as the fighting subsided, Israel proceeded to establish and develop its national institutions. The first elec-tions for the Constituent Assembly were held on January 25. 1949, and 120 representatives of 12 parties were elected to the Knesset (Parliament). The large number of parties reflected the diversity of thought and background of the people in Israel, whose founders were determined that it should be a democratic state with freedom of' speech. While all parties were pro-Israel, they differed in the intensity of their Zionism, in their economic policies, and in their relations to the Arabs. The Herut Party, for instance, representing the dissolved Irgun, held extreme views on capitalism and expansionism. They wanted control of all of Palestine. At the other end of the continuum were the Communists, who wanted complete equality of the Arabs. In between these two extremes were the large socialist labor parties, as well as other groups. As time went on new political formations and alignments appeared, as old ones disappeared and new splinters or new parties emerged. By 1969 even the Communists had split into two groups. Generally, the political mood shifted to the right as Israel found itself endlessly at war with its neighbors. While there was considerable factionalism in the new state, it was prevented from getting out of hand by the fact that all the parties received some of their funding from the Jewish Agency. Furthermore, dissension was greater within and among the Arab governments. The military defeats had dealt such a blow to Arab pride and self-confidence that internal instability and unrest resulted. Discontent with existing economic, social, and political conditions was also mounting. These dissatisfactions produced a military coup in Syria in 1949, the assassination of King Abdullah in Jordan in 1951, and the overthrow of King Farouk in Egypt in 1952. Israel also benefited from the rivalries between and among the various states. Transjordan had annexed the part of Palestine not conquered by Israel and King Abdullah saw his vision of a Greater Syria being fulfilled. But the Arab League denounced this annexation, and under Egypt's leadership an All-Palestine government was organized in the Gaza strip. The legislative measures that were passed in the first two years of the State of Israel had far-reaching implications for its development. Free and compulsory education for all children was initiated. A: conscription law required all youths, both male and female, to undergo at least two years of compulsory military training and service. Economic laws assumed a planned economy that aimed at control of all vital goods and services. Perhaps the most significant of early measures was the aggressive promotion of immigration into Israel, referred to by the Jewish Agency as "The Ingathering of the Exiles." The Law of the Return gave every Jew in the world the right to immigrate into Israel and to settle there permanently, and the Nationality Law provided for the acquisition of Israeli nationality immediately upon the return. The machinery for bringing in new immigrants was, of course, already in existence, but this had to be adapted te a rapidly changing situation and to a growing volume. During the three years between May 15, 1948, and May, 1951, some 600,000 Jews entered Israel (see Table 13), as compared with 452,157 during the previous 29 years of British Mandatory rule. Jewish population thus more than doubled in less than four years. The gigantic operation has been described by J. Hodess as follows: The task of "ingathering" undertaken by the Jewish Agency would have been enormous if the immigrants had come from only a few countries; but to direct and arrange transportation from 52 or more countries of persons with different habits of life and speaking 'diverse languages in three and one-half years necessitated world-wide machinery involving offices and representatives in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, Italy, France, England, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, Tunis, Tripoli. Emissaries, medical missions, arrangements for a luggage service, harbour storage, etc., all had to be provided.  Until 1948, 90 percent of the Jewish immigrants had been from Europe, but in the first three to four years after statehood had been proclaimed this dropped to 50 percent, the other 50 percent coming from Asia and Africa. After 1948 the position of the Jews in Arab countries underwent a considerable change. The Arab world was no longer a preferred haven for the Jews as had been the case for centuries. This was true for several reasons. A number of Arab countries were undergoing major social revolutions, which made conditions difficult for the propertied minorities, regardless of their religion or race. In addition, the attitude of many Arabs to the Jews in their midst changed as the Zionists established the State of Israel, which they saw as a wedge in the Arab world. The increasing economic and political discomforts felt by the Jews made them much more open to the "ingathering" program being vigorously promoted by the Jewish Agency. The first major transfer of Jews from Arab lands was from May, 1949 to September 1, 1950, when 45,000 Yemenite Jews were airlifted to Israel in the famous "magic carpet" operation, This was followed by the ingathering of 49,500 Iraqi Jews, again by special airborne operation. In all, over 300,000 Jews from Muslim lands, most of them Arabic in language and culture, arrived in Israel between 1949 and 1951. If immigration was a major achievement, absorption was a no less formidable task. While the exodus of 750,000 Arabs had left many openings for as many immigrants and more, not all of the newcomers could be assimilated into the labor force. Thousands of the immigrants were children, thousands more were old or sick, and many of these had to be housed in temporary camps manned by three thousand officials.Immigration and absorption required vast monetary resources, since many of the immigrants came penniless, being European victims of the war. Also, most of the Jews leaving Arab countries were forced to leave most of their assets behind. However, the task of the State of Israel was made easier by three kinds of resources: 1) the contributions of the Jewish Agency averaging about $100,000,000 a year (1946-47) and coming mainly from the US; 2) properties left behind by the Arabs (more will be said on this matter later); and 3) reparation payments by the West German government. Israel demanded one billion dollars from West Germany and a half billion dollars from East Germany, these being collective claims on top of the $175,000,000 already granted to half a million individual Jewish claimants. The final negotiated settlement committed West Germany to pay nearly one billion for goods and services assisting in resettlement and rehabilitation over a period of years. Israel, on the other hand, agreed to give preference to German commodities and services and also to consider the agreement as a final settlement, though the claims of individual Jews were not to be affected thereby." In addition to the material resources, Israel had an abundance of human leadership potential, and this was being rapidly expanded by western-type universities and technical schools. The resources facilitated the absorption of the immigrants in agriculture and industry. Nearly 500 new villages were established in Israel's first twenty years, as were numerous industries. From both agriculture and manufacturing there were substantial exports so that Israel's gross national product grew by an annual average of nine percent. Economically and culturally, the new State of Israel was indeed impressive. Thousands of acres of land were being re-claimed. Millions of trees were being planted. New crops were being introduced. Many miles of frontier roads were being built. Not only was Israel developing her own land, but before long she was also assisting in training: and development programs in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The rapid expansion of Israel's population (see Table 14) and the advance of her economy was as irritating to the Arabs as it was a source of pride and joy for the Jews. Although the Arabs had signed armistice agreements, these agreements only meant the end of military operations and not the recognition of Israel, certainly not the assent to all that Israel was doing in the name of her alleged sovereignty.  the sovereignty achieved, especially in Jerusalem, the most desired part of the national homeland. Some verbal concessions were made by Israel when she sought UN membership, for a condition of this membership was for Israel to allow internationalization. Shortly after Israel was admitted, however, she again opposed internationalization and proceeded to move more and more of her governmental agencies to Jerusalem. The Knesset held its sessions in Jerusalem, and on January 25, 1950, it announced that Jerusalem had been the capital since the first day of independence. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, as Transjordan was now called, was also opposed to any changes in the status quo, and eventually (in 1959) the Old City was proclaimed by Jordan as its second capital, though the central government remained in Amman. Additional efforts were made by the UN, and the western powers refused for a while to move their embassies from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. However, after the Soviet ambassador presented his credentials in Jerusalem in December of 1953, the US, Britain, and France soon followed suit. The status of Jerusalem after the 1949 Armistice Agreements was only one of the problems remaining. There were Arab-Israeli tensions at many places along the border. The earliest incidents were largely caused by individuals or groups with innocent motives. Bedouin tribes, who for centuries had freely moved through the Negev and other parts of Palestine, were suddenly told that they were trespassing, and Arab refugees seeking return to their villages to harvest crops, visit relatives, or claim sonic movable properties were told that they were infiltrators and treated as such by Israel. Other incidents arose because of inadequately marked demarcation lines. Some of these borders cut Arab villages off from their field:,. The teams of the United Nations Truce Super-visory Organization (UNTSO), established in 1949, were unable to prevent all incidents, especially as provocative Israeli patrols and poorly disciplined Jordanian police themselves crossed the lines. The governments on both sides at first took certain measures to prevent border incidents, but beginning in 1951 Israel develop-ed "a deliberate and official policy of retaliation," Period Immigration Population at end (if period Jews Non-Jews Total 1954 18,370 1,526,009 191,805 1,717,814 1955 37,478 1,590,519 189,556 1,789,075 1956 56,234 1,667,455 204,935 1,872,390 1957 71,224 1,762,741 213,213 1,975,954 1958 27,082 1,810,148 221,524 2,031,072 1959 23,895 1,858,841 229,344 2,088,685 1960 24,510 1,911,200 239,200 2,150,400 1961 47,638 1,981,700 252,500 2,234,200 1962 61,328 2,068,900 262,900 2,331,800 1963 64,364 2,155,500 274,600 2,430,100 1964 54,716 2,239,000 286,400 2,525,600 1965 30,736 2,299,100 299,300 2,598,400 1966 15,730 2,344,900 312,500 2,657,400 The changes that were being effected in Jerusalem were one major point of contention. The UN Partition Resolution had intended for the city to be internationalized, but during the Palestine War Israel had seized the new western section of the city while Transjordan occupied the smaller and older eastern sector containing most of the holy places. The armistice agreement between Israel and Transjordan accepted the situation as it was, since neither side was much interested in internationalization. There continued to be pressures for internationalization, however. The pope wanted it, as did Orthodox and Armenian- church leaders; and the USSR and other states favoring partition wanted the provisions for the Holy City implemented. Accordingly, the UN set up a Conciliation Commission for Palestine, whose duties among other things were to draw up proposals for an international regime for Jerusalem. In due course, the Commission recommended, however, that the Arab and Jewish sectors remain intact but that a UN commissioner for Jerusalem be appointed to ensure demilitarization and neutralization of the Holy City. But the, Jews were in no mood to neutralize or allow an international commission with authority over their sector of the city. Before 1948, the Jews had reluctantly relinquished their claim to Jerusalem, if only they could achieve statehood, but now they were determined not to retreat one foot from though full responsibility for these assaults was not assumed until 1955. By that time Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was openly contending that only superior force and "two-for-one" retaliation policies would keep the Arabs from infiltrating, meaning returning to their homes. As Fred J. Khouri has established with well-documented reports: In practice, Israel frequently went beyond the principle of"an eye for an eye" and sought to inflict many more casualties, on the Arabs than she had originally suffered. For example, on October, 1953, in reprisal for the murder of an Israeli woman and two children, Israeli military forces attacked the Jordanian village of Qibya, killing forty-two men, women, and children and injuring 15 other persons.... From the period of January 1, 1955 through September 30, 1956 UNTSO reported the following verified casualties: 496 Arabs killed and 419 injured compared to 121 Israelis killed and 332 injured."'Israeli attacks served a variety of purposes. They ensured a flow of financial and political support from world Jewry. They helped to strengthen national unity in Israel, and, at a time when unity was by no means to he taken for granted, Israeli political pressures were such that especially in election years more and larger reprisal raids were necessary. Sometimes the so-called retaliations were attempts to end Arab boycotts and blockades and to force Arab governments to come to terms with Israel. The economic boycott had its origin in a 1945 decision of the Arab League to boycott all Zionist firms in Palestine, and this was expanded after Israel became a state. Egypt, for instance, made it impossible or difficult for ships dealing with Israel to use either the Suez Canal or the Gulf of Aqaba. This handicap became one of the most impelling reasons for the Israeli invasion of the Sinai in October 1956. At that time Britain and France also had their grievances against Egypt. especially after President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal Company in July 1956. Other developments in that year forged a closer alliance between the western powers and Israel, while the Soviet Union was beginning to align herself with the Arabs. France had energetically been supplying Israel with arms, and this had led Nasser to seek arms from the United States. When such aid was not forthcoming in the desired amount, Nasser turned to the Soviet bloc for help and at the same time he recognized China. The US was so incensed that Secretary of State John Foster Dulles suddenly withdrew the US offer to finance the Aswan Dam, and so Nasser turned to the USSR also for aid on that project. In further retaliation, he nationalized the Canal, offered to compensate company shareholders:, and announced that Canal revenues would be used to help pay for the dam. An 18-nation conference, convened in London by the US, sought to set up an international authority to administer the Canal, but Egypt rejected the proposal as a continued infringe-ment on her sovereignty. Britain and France were enraged, not least of all because both countries were already smarting from the decline of their power positions elsewhere in the world.The moment was ripe for Israeli action against Egypt, and in October the government decided to initiate a preventive war against Egypt. Since Nasser had largely withdrawn his Sinai forces to protect the Canal against British and French inter-vention, the Israeli troops were able to make a deep thrust toward Egypt. At that point the British and French ordered both forces to withdraw ten miles from the Canal so that they could “protect it.” They ended up bombing Egyptian air fields and other military targets. Israel had hoped that the US, engaged as it was in an election campaign, would not antagonize Jewish voters, but Presi-dent Eisenhower could not support Anglo-French-Israeli action. Instead, he took the initiative in calling a meeting of the UN Security Council, which in turn called for a Special Emergency Session of the General Assembly. A resolution introduced by the US called for prompt withdrawal behind armistice lines of the Israeli forces, and the vote passed overwhelmingly with only Britain, France, Israel, Australia, and New Zealand voting against it.Pressures were also brought to bear on Britain and France with the result that they accepted a cease-fire on November 6. Israel reluctantly agreed to a cease-fire on November 8. Subsequent resolutions demanded immediate and unconditional withdrawal, which took until March 8, 1957 to complete. In the meantime, the UN passed a Canadian resolution setting up a United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF) to help keep the peace between the Egyptian and Israeli border. However, the peace was at best an uneasy one. Israel refused to allow UNEF troops on her soil because this would infringe on her sovereignty, and Egypt insisted on the right to have UNEF removed if she so chose, and such a choice was made in 1967. For several years after 1957 the Israeli borders with her Arab neighbors were quiet, but then the minor incidents and border conflicts increased, both in number and intensity. Each new incident between Israel and Egypt, Israel and Jordan, or Israel and Syria increased hatred and fear among both Arabs and Israelis. The unresolved refugee question remained a festering sore as Israel refused to abide by a series of UN resolutions relat-ing to the refugees. Jordan for her part refused free access to the Jewish holy places in the Old City - Israel complained that Jewish sites were being desecrated-and interfered also with the cultural and humanitarian institutions on Mount Scopus. Both acts were in contravention of the armistice agreement. Egypt continued to interfere with Israeli shipping in the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba, these having been two provisions which the Israelis had obtained assurances for from both the UN and the US. Early in 1967 the hostile attitudes and acts on the part of both Israelis and Arabs led to another major -crisis and the sixday military confrontation known as the June War. The events leading up to it included sharp confrontations between Syria and Israel. Syria supported Palestinian refugee commando activities, and Israel continued to send tractors to cultivate disputed lands in the demilitarized zone. On April 7 there was a major clash when Syria fired on what she said was an armed tractor in disputed territory and what Israel said was an unarmed tractor on Israeli lands. Israel responded with a large-scale reprisal action, and it was only with great difficulty that UNTSO could arrange a cease-fire.The April incident had important consequences. The Syrian military alliance with Jordan and Egypt of 1956 came into play, and Arab solidarity appeared to be greater than ever. In Egypt Nasser felt political pressures from both without and within, and on May 16 he began to move large numbers of troops into the Sinai. A few days later lie requested that the UNEF troops be withdrawn, and on May 22 he closed the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli ships. Israel complained about the UNEF withdrawal, but unlike Egypt, Israel had never accepted UNEF on her soil in the first place. Nor did 'Israel invite UNEF to locate on her side of the border at this time. Similarly, Jordan's King Hussein was being pressured to do more for the Palestinians, who constituted two-thirds of Jor-dan's population. On May 30 he traveled to Cairo and signed a five-year mutual defense pact. Meanwhile, the UN Secretary-General U Thant had convened a session of the Security Council where the Arab-Israeli conflict became a war of words, with thy Soviet Union now providing full backing for the Arabs. while the US stood behind Israel, committing ~herself to support the political independence and territorial~ integrity of that nation. As the crisis deepened in the Middle East - and it appeared in the West that the Arabs were about to push the Jews into the sea - Christian leaders who had been opposing American intervention in Vietnam now called for intervention on behalf of Israel. Sponsoring a three-quarter-page advertisement in the New York Times on Sunday, June 4, men like John C. Bennett, Martin Luther King, Reinhold Niebuhr, and Robert McAfee Brown called for "moral responsibility toward the Middle East" in view of the fact "that Israel is a new nation whose people are still recovering from the horror and decimation of the European holocaust." Majdia D. Khadduri has written: That Israel took the offensive in the war only increased the pressure on Christian leaders for moral support. In city after city, representatives of churches were called on to share the platform at meetings and rallies with rabbis and public officials and to affirm that Israel's cause was just.... This is nothing new. Over the years pro-Israeli interests have systematically cultivated the Christian clergy.... Clergymen wereoffered free trips to the Holy Land…. American Christian support for Israel could not, from Israel's point of view, have been more timely. On June 3 the cabinet had approved a massive military action, on June 4 the advertisement appeared, and on June 5 Israel once more initiated a "preventive war" and once again made full use of the element of surprise. Devastating air attacks were launched on military airfields in Egypt, Syria. Jordan, and Iraq. All of these were in a state of complete unpreparedness, and there was little evidence that the Arabs had been ready for a big push. With unchallenged control of the air, Israeli armor and mechanized infantry took the offensive and in a few days they conquered the Gaza Strip, the Sinai, Jordan's West Bank, and the Golan Heights in Syria. Meanwhile, the UN Security Council :was in session calling for a cease-fire. With most or all of her immediate military objectives achieved, and under pressure from the UN to cease hostilities forthwith, Israel agreed to a cease-fire on June 11. For Israel the June War had been an overwhelming victory and for the Arabs a most humiliating defeat. While Israel had 679 soldiers killed and 2,563 wounded, the Arabs had lost far more, both civilian and military casualties. But in spite of Israel's triumph none of the basic issues in the dispute were settled. The Arab states were only temporarily defeated, and their-defeat now united them more than ever. The war brought Hussein and Nasser together. and Saudi Arabia as well as other oil-rich Arab states were helping Egypt in the economic crisis resulting from the closing of the Suez. The big powers were more committed than ever. The USSR was determined to rearm the Arabs, and the United States was more than ever linked to Israel. Most important of all, the War had created many new refugees on Israel's borders, and brought within her own occupied territories 540,000 Palestinian Arab refugees and another 500,-000 Jordanians, Egyptians, and Syrians. Hatred against Israel was greater than ever and there was even danger that tile approximately 314,000 Israeli Arabs in Israel proper, who had until then not been a major security factor, would now become restless. At first Israel gave the impression that she had no permanent interest in the occupied territories, but the Old City of Jerusalem was annexed on June 29 and developments in the other territories likewise suggested permanent intentions. While Israel took these actions, as she said, in the interest of security, her insecurity was really greater than ever. On three fronts (Egypt, Jordan, and Syria) and sometimes five (Lebanon and internally as in Gaza) there were positions to hold and borders to be guarded (see Map 12). By the end of 1969 the attacks and counterattacks of pre-June War days had increased in frequency as well as magnitude.  In the meantime, the United Nations had again worked out a peace formula as best it could and commissioned its representative, Gunnar Jarring of Sweden, to mediate, reconcile, and implement. The peace resolution commissioning the representative was passed by the UN Security Council on November 22, 1967, just one week before the 20th anniversary of the partition resolution. The new plan asked Israel to withdraw its forces and toprovide a just settlement for refugees. The Arabs, on the other hand, were asked to guarantee freedom of navigation through international waters as well as the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence of Israel. Said the resolution: The Security Council, Expressing its continuing concern with the grave situation in the Middle East, Emphasizing the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war and the need to work for a just and lasting peace in which every state in the area can live in security,Emphasizing further that all member states in their accep-tance of the Charter of the United Nations have undertaken a commitment to act in accordance with Article 2 of the Charter. 1. Affirms that the fulfillment of Charter principles requires the establishment of a just and lasting peace in the Middle East which should include the application of both the following principles: (i) Withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories of recent conflict; (ii) Termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for an acknowledgement of the sovereignty, ter-ritorial integrity and political independence of every state in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force; 2. Affirms further the necessity (a) for guaranteeing freedom of navigation through international waterways in the area; (b) for achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem; (c) for guaranteeing the territorial inviolability and political independence of every state in the area, through measures including the establishment of demilitarized zones; 3. Requests the Secretary General to designate a special representative to proceed to the Middle East to establish and maintain contacts with the states concerned in order to promote agreement and assist efforts to achieve a peaceful and accepted settlement in accordance with the provisions and principles in the resolution; 4. Requests the Secretary General to report to the Security Council on the progress of the efforts of the special representative as soon as possible." The resolution appeared to suggest the best possible way to peace with minimum compromises on either side. However, there was no way to begin. Israel insisted on talking directly with the Arabs before making any move, and the Arabs insisted on withdrawal from occupied territories and the return of refugees before talking. Israel insisted from June 29 on that the issue of Jerusalem and other matters were not negotiable, and so the Arabs were even less disposed to coming to the conference table. Since the powers in the Middle East themselves were not moving toward peace and since the UN also lacked the potency to achieve a settlement, the Big Two (.USSR and US) or the Big Four (also France and Britain) were meeting in 1969 in search of a peace formula. Their major handicap, however, was their lack of credibility. By that time all of the powers had switched sides at least once, and if the United States had not switched sides, she had, at one time or another, been engaged in arming both sides.The United States, more than any other big power, appeared to hold the key to a Middle East settlement, but when at the end of 1969 she urged Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories and the repatriation of refugees, Israel denounced her as she had earlier denounced the talks of the Big Two and the Big Four. For the United States, the strong reference to the priority need for a settlement of the refugee problem was a new emphasis. Along with most of the world she was coming to the conclusion, somewhat belatedly, that at the heart of the Middle East problem was the injustice done to the Palestinian Arabs in the process of providing in Palestine a new homeland and statehood for the Jews. Several months later, however, the main focus again was on armaments, as both the USSR and the US became militarily more involved than ever, and the solution to the Middle East conflict seemed farther away than ever. The Palestinians seek only the right to live in peace in the land that is their home. When the Israeli leaders relinquish their narrow, chauvinistic aims and recognize the fundamental rights of the Palestinians, a compromise will be possible and peace will return to the Land of Peace.-Karin Hautoum A good case could be made for concluding our historical summary with a focus on the Arab states vis-a-vis Israel or on the growing involvement of the super-powers, inasmuch as the Middle East problem consists of several layers of con-flict. However, it is necessary at all times for the historian to address himself to the most fundamental forces at work. It is the present writer's assessment, further to be clarified in the final chapter, that the most basic confrontation in the Middle East is not between the United States and the Soviet Union or between Egypt and Israel, but rather between Israel and the Palestinians. At the end of the 1960s it was necessary to speak of two groups of Palestinians, those inside of Palestine and those outside of Palestine, a total of nearly three million people (see Table 15). Those inside of Palestine could also be divided into two groups: the approximately 314,000 Arabs who resided within the borders of the State of Israel as established by the 1949 Armistice Agreements -and the: approximately 992,000 who came under Israeli occupation as a result of the June War as can be seen from Table 16. More will be said about these later. While the number of Palestinians remaining inside of Palestine numbered in excess of 1,300,000, the total Palestinian population was more than doubled by those outside the country, as can be seen from Table 17.  * As estimated by Arab information Office. Ottawa. Of the total, over 1,300,000 were classed as refugees according to the registrations of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East. More than half of these refugees were outside the country (see Table I8).  Notes: 1) Figures in parentheses are as of June 1, 1967, i.e. before June 1967 hostilities. 2) This figure includes about 40,000 refugees still reported in Gaza, but who have left since the hostilities to live in various countries. The exodus of Palestinians from their homelands took place in two major stages. The first was in 1947 and 1948, when around 700,000 Palestinians left their homes. The second was in 1967, when 150,000 of these original refugees were displaced a second time, and another 150,000 Palestinians, 100,000 Syrians, and 35,000 Egyptians became refugees for the first time. The first exodus in 1947-48 in itself consisted of several phases. About 30,000 higher-class Arabs, mainly from Haifa and Jaifa, remembering the bloody skirmishes in the 1930s, left immediately after the UN General Assembly Partition Resolution on November 29, 1947. In doint, so, they expected to return, as they did in the 1930s, after calm had been restored. This time, however, they could not return. The loss of these key people, in the Arab community left a leadership vacuum, and, as the fighting spread and intensified, other thousands of frightened Arabs left their homes. After the Irgun and Stern Gangs massacre at Deir Yassin on April 9, 1948, Arabs throughout the country "were seized with limitless panic and started to flee for their lives," according to Menachem Begin, the commander of the Irgun forces.' By May 15, some 200,000 Palestinians had already become refugees.After Israel proclaimed its statehood and the Arab armies joined the irregulars in opposition to the partition of Palestine, the Arab exodus gained considerable momentum. By the time of the second truce in the middle of July only about 170.0011 Arabs remained in Israel. Israel maintained that tile cause: for the Right of so many Palestinians was that Arab leaders wanted it that way. Accord-ing to Israel, Arab leaders had given such orders for three reasons: (1) to clear the roads and villages for the advance of the regular Arab armies; (2) to demonstrate the inability of Jews and Arabs to live side by side; and (3) to disrupt services at the end of the Mandate and thus make impossible the peaceful formation of the Jewish State." The Arab claim, reported by Khouri, was that Israeli au-thorities "used both military force: and psychological warfare to compel as many Arabs as possible to leave their homes."" In the western world, the Israeli viewpoint concerning the refugees was the one that was most promoted and most believed. Thus, only after 1967 did it become clear that only one side of the story had been heard. As John H. Davis, the former Commission-General of UNRWA reported: General Glubb has pointed out, voluntary emigrants do notleave their homes with only the clothes they stand in, or in such hurry and confusion that husbands lose sight of wives and parents of their children. Nor does there appear to be one shred of evidence to substantiate the claim that the fleeing refugees wore obeying Arab orders. An exhaustive ex-amination of the minutes, resolutions, and press releases of the Arab League, of the files of leading Arabic newspapers. of day-to-day monitorings, of broadcasts from Arab capitals and secret Arab radio stations, failed to reveal a single ref-erence, direct or indirect, to an order given to the Arabs of Palestine to leave. All the evidence is to the contrary; that the Arab authorities continuously exhorted the Palestinian Arabs not to leave the country.... Panic and bewilderment played decisive parts in the flight. But the extent to which the refugees were savagely driven out by the Israelis as part of a deliberate master-plan has been insufficiently recognized. Considering the Israeli point of view it could hardly have been otherwise. The entire Zionist scheme of establishing a state dominated by Jews would have faltered without the Arab eviction. In the Jewish State, authorized by the UN, the Arab population would have been almost equal to that of the Jews 495,000 to 498,000. Within the boundaries established by the Armistice, the Arab population, without the exodus, would have been 892,000 compared to 655,000 Jews. As it was, the immediate interests of the Zionists could not have been served better than by the departure of the majority of the Arabs. The Jews became a decided majority. Some 350 Arab villages lay vacant for the arrival of thousands of Jewish immigrants, and the refugees left behind two,-thirds of the cultivated land acquired by Israel. The value of all abandoned Arab property in Israel was conservatively estimated by the United Nations at $336 million. The 700,000 displaced Palestinians placed an enormous burden on the neighboring Arab states, and they did what they could to help the refugees. However, the task was too great for the meager resources of the young and relatively poor Arab states, who appealed to the UN for help Count Bernadotte, the UN Mediator, initiated an emergency relief action under the UN Director of Disaster Relief, but his main attention was given to refugee repatriation as the best relief of all. He appealed to Israel to receive the refugees on the promise that the UN would screen them and eliminate potential security risks, but Israel refused precisely on grounds of security. When repatriation did not become immediately possible, the UN on December 19, 1948 authorized the appointment of a Director of UN Relief for Palestine Refugees, approved emergency funds of five million dollars, and asked member states to provide an additional $32,000,000. A year later, when the refugee problem was still unsolved, the UNRPR was succeeded by UNRWA, the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, which was authorized to spend up to $54,900,000 on a relief and works program during an initial 18-month period.The United Nations was still assuming that the refugees would be repatriated Count Bernadotte had established the right to repatriation as one f the seven basic premises for peace. He successfully asked the UN to establish a Conciliation Commission, which would have as one of its functions the supervision and assistance of repatriation and rehabilitation of the Arab refugees, or the compensation for property lost of those who would choose not to return. Said the Third General Assembly of the UN: ... the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so atthe earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return andfor loss of or damage to property ... the Conciliation Com-mission to facilitate the repatriation, resettlement, and eco-nomic and social rehabilitation of the refugees and the pay-ment of compensation....The resolution set forth the UN policy toward the Arab refugee. It became the basis for most statements that define UN relations to the refugee problem, and it has been cited at each regular session of the General Assembly since 1948. Still bitter over the Partition Resolution, the Arabs at first were not enthusiastic about any UN action, but by early 1949 they became strong advocates of UN implementation of the refugee resolution. Israel refused to act until the Arab states would conclude a peace settlement, and the Arab governments in turn insisted on repatriation before there could be any negotiations. The result was a complete stalemate on the question of repatriation, except for the reunification of some 40.000 Arabs with their families. Arab leaders maintained that this action was insignificant in that at least 35,000 of the number were Palestine Arabs, who left their homes during the height of the 1948 conflict but remained within the area that is now Israel."As early as one month after the declaration of independence, Israeli Prime Minister Ben-Gurion took the position that no refugee should be returned, and the promotion of immediate and large-scale immigration was intended in part to make a return impossible. In other words, the policy of the fait accompli was pursued also in this area. Early in 1949, western and UN officials became quite impatient with Israel, and in a strong note to Ben-Gurion on May 29, 1949, President Truman expressed his "deep disappointment at the failure" of Is-rael to make any concessions on the refugee issue, "interpreted Israel's attitude as dangerous to peace," insisted that "tangible refugee concessions should be made now as an essential preliminary to any prospect for a general settlement," and threatened that "the United States would reconsider its attitude toward Israel." The pressure from the United States catwed Israel to modihy her position, but two of her own suggestions proved unacceptable to the Arabs, the United States, and the UN Con-ciliation Commission, and nothing came of them. The first was an offer to return the refugees of the Gaza Strip in exchange for sovereignty over the area. The second offer suggested a return of 100,000 refugees, provided Israel could choose the place of their resettlement and the Arab states would consent.Other efforts were made to get Israel to accept repatriation, but in July 1950 Israel announced- that she was no longer bound by former offers regarding the return of Arab refugees since "the context in which that offer was made had disappeared." Four months later Abba Eban told the UN Ad Hoc Political Committee: As months and years passed without any agreement from the neighboring states to negotiate a peace settlement tile possi-bility of any substantial restoration of the conditions existing before the war steadily diminished, in the eyes of all qualified observers. Life had not stood still. It had moved forward with headlong speed. A vacuum does not endure. The UN resolutions not only provided for repatriation, but also spoke of resettlement and compensation for lost or damaged property of those who were unable or unwilling to return. As already indicated, the Arabs left behind substantial holdings. These included whole cities like Jaffa, Acre, Lydda, Ramleh, Baysau, and Majdal, 388 towns and villages, and large parts of 94 other cities and towns. Some 10,000 shops, businesses, and stores were also left behind. Eight percent of Israel's total land area represented land abandoned by the Arab refugees, and fruit produced on Arab lands provided nearly 10 percent of Israel's foreign currency earnings from exports in 1951. Israel's attitude to Arab properties was determined not only by security and social considerations but also by economic factors, for "during its formative years the new state's economy hovered constantly on the brink of bankruptcy." The funds provided by world Jewry through the Jewish Agency, the German reparation payments, the grants-in-aid from the United States government, and other foreign loans supplemented very handily the native Jewish resources; yet they were insufficient. The fields, orchards, vineyards, shops, factories, and businesses left behind by the Arabs, therefore, were made to order for the new Jewish immigrants, who needed. She lter, food and employment; and the Israeli government readily turned to these new resources to meet its own emergencies, In llecem15er 1948 the office of the Custodian of Abandoned Property was established by Israel. It was his task to be in charge of all movable and immovable property belonging to, controlled by, or even occupied by "absentees," who were described as follows: ... any owner who on November 29. 1947, was a citizen of Lebanon, Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Transjordan, Iraq, or the Yemen; or who on that date was in any part of Palestine not Israel or Israel-occupied territory; or who on that date was a citizen of Palestine and had left his normal place of Palestine without a certificate exempting him from the status of absentee. Also defined as absentee was any company, part-nership or association if at least half its Members were absentees or if at least half its capital belonged to absentees. In other words, the Custodian was placed in charge of all property that Arabs were not bodily present to claim as their own as of November 29, 1947. While this ordinance was promulgated before the large flight of refugees and initially applied only to nonresident owners or resident owners temporarily abroad, it reflected the attitude of Israel and the eagerness with which it reached for accessible Arab real estate. Israelis finance minister stressed that the Israeli legislation was patterned on that of Pakistan and India following partition in that part of the world in 1947 with resultant vast exchanges of' population. While properties legally belonged to the absentees, the Custodian used them for incoming refugees. By July 1950 at least 170,000 persons, mostly new immigrants, had been housed in premises under the Custodian's control, and 7,800 shops and stores and offices had been sublet to new arrivals. After November, 1949, the Custodian operated under a new bill affecting the property of all persons who had fled, meaning all refugees in addition to the absentees. This new measure also permitted the Custodian to sell the property to a State Development Authority at prices not less than 80 percent of the value. These resources, it was at first assumed by some Knesset members and other leaders in Israel, would be used to compensate the Arabs. But compensation was at first hindered by disagreement in Israel itself and then by disagreement on the method of compensation between Israel and the Arab states. Israel insisted that "any funds that it agrees to defray for compensation be credited to the integration fund instead of being, dissipated in individual payments." Compensation, in other words, was to be paid in a lump sum to an agency of the UN. This procedure was rejected outright by the Arab League, which demanded that compensation be paid the refugees individually by those persons in Israel "who have robbed them of their property." Damage to property was also to be paid, as well as a rental fee for the use of the property in the interim period. As an agreement on compensation was delayed, Israeli absorption of Arab property continued through the sale of such property according to the latest ordinance and the policies of the Development Authority. Through these policies not only the property of absentees and refugees was being absorbed but also land belonging to Arabs still in Israel. The latter often came under the jurisdiction of the Custodian or the Authority for security reasons or the development of Jewish collectives under the Land Acquisition Law. In this way some 30,000 Arabs legally residing in Israel lost access to part of their lands, though some of it was rented back to them on a yearly basis. In 1951 the approach of the Israeli government hardened even more than before, when Arab Iraq set up a Custodian of Jewish Property with power to control the properties of the departed Iraqi Jews. One hundred thousand of these Iraqis were now in Israel, and their 15,000 influential members of the intellectual, professional, and capitalist class became a powerful pressure group. In their opinion th;t property abandoned by Jews in Iraq was about equal to that abandoned by Arabs in Israel. Their argument was persuasive, and from that time on Israelis frequently suggested that the books could be closed on refugee repatriation and compensation, inasmuch as a fair exchange of population and property bad been affected. The Iraqi Jews and Israel may have considered this a fair deal, but for the Palestinians now located mostly in UNRWA refugee camps justice had by no means been done. Through UNRWA, the Arab League, and sympathetic governments they continued their efforts in the desired direction, but every passing year made either repatriation or compensation more difficult. After 1956 Israel linked any further consideration of com-pensation to the abandonment by the Arab states of their economic boycott against Israel. The only concession made by Israel was the partial release of some $7.5 million of the total held in Arab-blocked accounts, as well as the contents of some safety boxes, a tiny fraction of the total of abandoned Arab property. As both repatriation and compensation were delayed, various efforts to settle Palestine refugees in Arab lands were made, this also having been a provision of the UN General Assembly's basic resolution in 1948. Support by some UN member states for resettlement was vigorous already in 1949. The appointment in that year of an Economic Survey Mission had resettlement as part of its goal. The Mission was headed by Gordon Clapp, a former chairman of the board of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The Conciliation Commission and the Clapp Mission assumed that if economic problems could be resolved political tensions would be eased. Clapp proposed a program of public works in the countries where the refugees were situated. This program was calculated to improve the productivity of the areas while continuing relief until all refugees could be absorbed. The proposals were reflected in the name of the new agency established as a result and to which we have already been introduced, namely: the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). The initial $59 million fund was supplemented by $30 million in 1950, and in 1951 a three-year program costing $200 million was approved - $50 million for relief and $200 mil-lion for reintegration. Relief was to be progressively reduced until it would amount to only $5 million in 1954. The hope of the UN was that there would be a gradual transfer of responsibility from UNRWA to the Arab states when the refugees would already be largely self-supporting. However, for both the Arab states and the Palestinian refugees the assumptions of the Clapp Mission were false. To them economic factors were not the most important. The development projects were viewed with suspicion, And to support them, the Arabs believed, would undermine the right of the refugees to return to their homes in Palestine. No progress was, therefore, made on the major development schemes, and at the end of 1954, the target date for ending relief, only 8,000 refugees had been made self-sufficient and less than $10 million had been used on "works" of the UN agency. The Arab states on the whole had their own political reasons, apart from the humanitarian considerations, for wanting the Palestinians repatriated. The refugees posed internal economic, social as well as political problems for such host governments as Lebanon, Jordan, and the United Arab Re-public (meaning Egypt and Syria) especially after 1958.In Lebanon the 126,485 Palestinians represented 8.4 percent of the country's population. These refugees, mostly Mus-lims, were threatening to upset the delicate balance between almost evenly divided Christians and Muslims in the country, with the Muslims challenging the Christians fur control. The Lebanon government, therefore, did not grant political rights to Palestinians, who were granted only residence visas and who had to hold special identity cards. Work permits were also difficult to obtain, although many Palestinians worked. The United Arab Republic granted most civil rights to Palestinians-that is, they had access to the courts-but political -rights were not granted. In the Gaza Strip (25 miles long and 5 miles wide), really a vast refugee camp under Egyptian military control and not included in the 1958 UAR union, the movement of Palestinians was severely restricted, as it was under the four-month Israeli occupation in 1956-57. An elective Legislative Council was formed in 1958, but all actions of the council were subject to the approval of the Egyptian Governor-General. Only in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, both East Bank and West Bank, did Palestinians enjoy full citizenship with voting rights. For Jordan there really was no alternative since the bulk of Palestinian refugees were in Jordan; and, added to the West Bank Palestinians, they constituted more than one half of Jordan's 1.6 million population. The citizenship status of Palestinians was unaffected by the federation of Jordan and Iraq in 1958, but it tended to reduce their considerable political power in Jordan. The refugees were also adversely affected by the power play between the United Arab Republic and the- Iraqi-Jordan federation, since the Palestinians in the federation tended to be pro-Nasser, and their politics were more anti-Israel than Jordan's. In the absence of repatriation and resettlement, the Palestinian Arabs remained the wards of UNRWA and the inter-national community.. This does not mean that the host governments did not assume responsibilities. On the contrary, by 1968 Jordan, Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon had spent more than $100 million "in direct assistance for health services, education, campsites, housing, roads, and security. Nor were the refugees themselves negligent or irresponsible as has been frequently insisted and commonly believed in the West. The evidence is to the contrary, according to UNRWA Commissioner-General John H. Davis: Following the upheaval of 1948, virtually all able-bodiedmale refugees who possessed skills needed in Arab countries or, for that Matter, elsewhere, found jobs almost immediately and became self-supporting and have never been dependent on international charity. This group comprised some 20% of the total working force which left their homes in Palestine in 108-1949; for the most part they were persons from the urban sector of Palestine, their good fortune being that the world needed the skills which they possessed. It was difficult, however, to provide employment opportunities for Arab farmers, for in the vicinity of the camps there was little: available arable land. The Arab countries themselves had a surplus of peasants, given the then available land resources and the exploding population. The Arab population in the camps burgeoned. More than 500,000 new refugees were born in less than twenty years, increasing the registered refugee population to 1,395,074 by July 1, 1969. The exact number of Palestinian refugees away from their homeland has always been a debatable figure. In the first place UNRWA never registered all of them, and in 1969 Arab Information Offices estimated, as has already been pointed out, that this unregistered sector of the Palestinian population had increased to about 400,000, admitting that this figure was somewhat arbitrary. Some uncertainty also arises from the fact that UNRWA was confronted by inevitable duplicate and false registrations. Allowances and adjustments were made for these annually for a total of some 58,000 from 1950 to 1968. Even so it knew that its rolls might be further inflated by some concealment of refugee deaths; But UNRWA could not rectify the situation because no census could be undertaken without the permission of host countries and refugee leaders. In general the Arabs tended to exaggerate the numbers of refugees entitled to relief, and Israel tended to minimize them, the latter estimate usually falling some 300,000 short of Arab estimates. In the Gaza Strip, however, which Israel held from November, 1956 to March, 1957, the UNRWA figures were not challenged by Israel. It should also be said here that the total UNRWA registration of 1,395.674 (1969 figure) included only 806,366 full-ration recipients. Half-ration recipients numbered 13,466 while babies registered for services numbered 326,185. The registered refugees receiving no rations or services numbered 148,004 while others receiving only partial services totaled 101,053.The cost of the services to the refugees in 64 camps (see Map 13) including food, shelter, medical and welfare services, and education for the refugee children was covered by special governmental and nongovernmental grants to UNRWA, averaging less than $40 million a year after 1950. Even so they were difficult to raise annually, in spite of the fact that food costs were kept at an average of seven cents a day per refugee.  About 70 percent of the UNRWA support came from the US, with the United Kingdom and Canada standing second and third as contributors. The Soviet Union and its allies have never contributed to the support of the refugees, and only with its realignment with the Arabs in 1957 did the USSR begin to demand repatriation and compensation. The lack of UNRWA funds presented this agency with the constant need to keep its services at a minimum and occasionally even to cut back. In spite of its meager resources UNRWA performed a gigantic service for the refugee population. Death rates and sickness were kept below the average in the Arab world. General education, vocational and teacher training, as well as university education were provided for nearly half a million young people. What UNRWA could not do was to make the Palestinians happy. Almost all continued to express their desire to return.The feeling that injustice had been done increased rather than diminished with the passing of time. The Palestinians continuedto hope and assume that the Arab governments would help them to go back as they said they would and that the UN would also facilitate the return, which it said annually was the right of the refugees. Palestinian feeling and frustration was well expressed before the UN Special Political Committee by a Christian Arab doctor in exile, Izzat Tannouns, as follows: I happen to be a Christian Arab of Christian parents born in Palestine. My home is in Jerusalem where; I lived all my life. I am not permitted to go back by the Israelis, not because I declared war on any country, not for occupying other people's homes; and not for persecuting the Jews, but for the simple reason that I was not born a Jew. While American Jews, Austrian Jews and even Arab Jews can go and occupy my home today I cannot do so because I am a Christian. The Jewish faith is the only valid visa to go and live in Israel today. Did you ever conceive that this could take place in this twentieth century, the century of the Declaration of Human Rights, the era of religious tolerance? I had the honor to tell this committee last year and I will tell it again this year, that my home is only 300 yards away from the armistice line and my clinic is on the other side of the road. ... I see people in them, people coming and going but I cannot move an inch forward. If I do l will be killed and my body will be labeled "guilty of the Criminal Act of Arab infiltration." This infiltration, Mr. Chairman, into one's own home, land, farm, and country has been the cause of the death of hundreds of my countrymen by people who, only a few years ago, were total strangers to the land. Moreover, this home of mine is being offered to any Jew in the world, be he from Warsaw, Tokyo or the West Indies, if he will condescend to go and take it. The Palestine Arab refugee problem is the transplantation of one people of one faith in the place of other people of other faiths through the force of arms. It is the problem of religious discrimination.... How can we improve the political atmosphere to begin peace talks of any kind if we are still prevented from reaching our homes? The mere discussion of "right of return" will be a "psychological road block" to a solution.... It is the duty of the United Nations before it is too late to place the Palestineproblem in its proper perspective. With the June War of 1967 the attitude of the Palestinians changed dramatically. They now saw that the world had not prevented the complete takeover by Israelis of their land, which they knew all along had been part of the Zionist plan. Indeed, they assumed after 1967 that the Greater Israel called for even more territorial acquisition in East Bank Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Again, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution asking Israel to allow the new 1967 refugees to return to their homes in the occupied area. Eighty-five percent of those 245,000 who had fled to the East Bank of Jordan filled out applications asking to return, but only about 15,000 were admitted by Israel. Although the Palestinians had been organizing, training, and dispatching groups before 1967, the fedayeen movement now gained strength dramatically. The desire and determination to return to their homelands was finding an enthusiastic military expression. So strong had the movement become that the politics and military strategy of the Arab states was by 1969 almost completely dominated by the Palestinian determination to have justice done. Yasir Arafat, the leader of Al-Fatah, the strongest of the Arab commando movements, was attending Arab summit conferences and generally being treated like a hero and head of state. The liberation movement also had its supporters in Israeli-occupied territories, so that Israel's security problem had a new dimension for that reason after 1967. There was now a real possibility that Al-Fatah, some Arab states, and the Arabs in occupied territories would rise up to crush the State of Israel, as they had threatened to do since 1948. In the interests of her security. Israel was, therefore, conducting almost daily jet raids across the Suez and the Jordan. The Syrian region too was being bombed and strafed, and Lebanon, which in 1969 gave more operating freedom to Al-Fatah, was likewise threatened. Inside Israel and the occupied territories security was being tightened. Land was being seized, Arabs were being evicted, and buildings were being demolished all in the name of security. Arabs were constantly being searched, and neighbor-hood punishment (meaning demolition of houses) was in 1969 instituted where neighbors were believed to have withheld information about commando activities. As in the past, so in 1969 Israeli retaliation, however, was producing exactly the opposite of the intended effect. In-stead of suing for peace the Arabs were preparing for the inevitable war with Israel. While they knew that Israel's military superiority might win her another round or two they were confident that in the long run the victory would be theirs. Meanwhile, the UN and the big powers stood by increasingly helpless as hate and hostilities in the Middle East escalated to a point of no return. The return that most peacemakers were seeking was to the status quo before the June War of 1967. Others, however, knew that the promise of Middle East peace had been destroyed already in 1947 with the UN Partition Resolution and before that by the Balfour Declaration of 1917. But even the return to 1967 had become impossible, and peace was nowhere in sight. I look forward, and my people with me look forward, toa future in which we will help you and you will help usto develop the land which is close to both our hearts....-Prince Feisall Peace can come only if Israel and Ishmael can feel that they are brothers. -Juda L. Magnes The foregoing historical review has revealed the prominence of God or gods in the minds of men in the long history of the Middle East, and so it is desirable and perhaps even necessary that we return to that theme once more as a way of seeking the best possible understanding of the problem and the most helpful insights relative to its resolution. In so doing, we will not produce a theological treatise but rather continue with the historical method, albeit with some theological intent on the assumption that North American Christians will in all likelihood be reading this book first and most. This audience has been chosen as a primary target for several reasons. First is the fact that many works for general audiences have been written and published in recent years. Second is the belief that it is precisely the Christian community which needs the longer historical view, the broader theological perspective, and a more creative international political concern. Third is the knowledge that the theology and politics of Christians have had in the past, and may have in the future, profound effect on western policies with regard to the Middle East. Having expressed this optimism about the Christian role, it is necessary to recognize first of all that the Christian com-munity comes to the Middle East situation with some very dis-tinct handicaps. The first of these is a rather sad record of past involvement, which appears to have had the character of imperialism. One needs only to review the policies of the various rulers of various empires who in one way or another contributed to the Middle East conflict - the emperors of Rome and Byzantium; the popes of the Crusades; the tsars of Russia; Napoleon of France; Wilhelm of Germany; Balfour, Churchill, and Attlee of Britain; Wilson, Truman, et al., of the United States. All of them wanted to establish order in the Middle! East. all of them explicitly or implicitly in the name of God. All of them had the direct and indirect benefit of Christian advisors. And all of them contributed to the present mess in the unfortmiddle of our world. The future Christian contribution to the resolution of the Middle East conflict must be and can be of a different order than what has been in the past, but the historical record will remain a handicap. The effects of the Crusades, or of the French imperial protection of Latin Christians, or of British imperial intervention, to name only a few examples, are with us to the present day. As the Jordanian paper al-Manar re-minded us in 1964:Our memories and experiences of Christians of the West arecompletely different [from those of the East]. They include the memory of Lord Allenby planting his sword in the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem and boasting "Now end the Crusades!" They include the memory of General Gourand putting his foot on the tomb and exclaiming "We have returned, 0Saladin!" Apart from the regrettable role that Christians have played in relation to the ambitions of their nation states, they have a special handicap with respect to Arabs, particularly Muslim Arabs, and to Jews. Both of these peoples are Semites. The historical record shows a great deal of Christian hostility toward Arabs and Jews, both of whom have been related to the anti-Christ. Both have experienced Christianity at various times and places as: anti-Semitic. Both have been the targets of rather imperialistic Christian --conversion attempts, and only recently have relationships been described as "conversations." As a bitter communication from Israel, addressed to the West, recently reviewed the Christian approach to the Jews: "Your inquisitions, pogroms, expulsions, the ghettos into which you jammed us, your forced baptisms...." Understandably, therefore, both the Jews and the Arabs are not easily ready to listen to Christian proposals for the resolution of the Middle East conflict. Any suggestion to the Palestinian commandos that they lay down their arms, so as not to threaten the security of the Jews, quite properly produces the rejoinder: "It was largely your arms that drove us into the desert" and "where were you during the 20 years that we were relatively pacifistic waiting for justice to be done without our resort to arms?"--, The "I-lymn of Hate" of a Palestinian Arab writing about his occupied homeland expresses Arab disappointment with the Christian West equally directly: If Jesus could see it now, 'He would preach jihad with the sword! The land in which He grew Has given birth to a million slaves. Why does he not revolt, Settle the account, tooth for tooth and eye for eye? In spite of all His teachings, The West's dagger is red with blood. 0 apostle of forgiveness! Dazed by calamity, I do not know the answer: Is it true you lived to suffer? Is it true you came to redeem? O apostle of forgiveness! In our misfortunC. Neither forgiveness nor love avail." Similarly, the Jews are apt to respond with their own criticisms to every Christian suggestion that Israel give its attention to justice for the Arabs. They are quick to charge that Christians have always been ready to talk justice to Jews, but always reluctant to offer justice to Jews. Even more disarming is the frequently heard accusation that the Christian critique of Zionism or Israel's doings is but a thinly disguised anti-Semitism. We say disarming, because every Christian in the West would rather be called by any other name than anti-Semite, for anti-Semitism is associated in minds of all the world with the worst evil of all, the Nazi holocaust. Zionists know this and use very effectively the subtlest hints of anti-Semitism to intimidate even the mildest critics. Unless the Christian remembers that criticism of a Jewish state or the Jewish people is not necessarily anti-Semitism, and that all Christians are not guilty of genocide any more than all Jews are guilty of deicide, he is, indeed, handicapped. Unless he can accept the past failures of Christians with humility and then rise above them with courage there will be very little for him to say or do. The Christian comes to the Middle East conflict, however, not only with severe handicaps but also with distinct assets, which permit him to disregard, refute, or overcome the blame which is so easily directed his way. These assets, like the liabilities, are related to both sides of the conflict. On the one hand are the conversational relationships that Christians and Jews have established in the West, particularly since World War II. In numerous cities in North America and in a variety of ways, Christians and Jews have engaged in useful dialogue and common social action projects. Indeed, Christians in America have in the twentieth century helped Zionism to achieve the goal of establishing a national homeland in the same way that British Christians in the nineteenth century prepared the way for the acceptance of the Zionist dream. And in the 1967 June War, the majority of Christians in North America accepted and promoted the popular interpretation that little David (Israel) had once more defeated the giant Goliath (the Arabs) with the help of God, the weekly Christian Century magazine being one of the very few exceptions. The analogy of David and Goliath was incorrect because it was Israel and not the Arabs that had military superiority; but that is, for the time being, beside the point. The point is that Israel enjoyed nearly universal Christian empathy in North America in 1967 as in 1947, and Zionist condemnation of its Christian critics for the sins of the past are only frac-tionally relevant. As North American Christians went to battle against the enemies of the Jews in Europe in World War II, so their hearts, rightly or wrongly, were on Israel's side in the most recent confrontation with the Arabs. A record of anti-Semitism is, therefore, only one side of the coin, and maybe not even the complete side at that, the other side being a strong element of pro-Semitism, vis-a-vis Israel. This strong western inclination toward Israel is. of course, well known by the Arabs, which means that western Christian liabilities arC by that fact substantially increased in the Arab world. However, even there Christians are not without ad-vantages, for they do have a;#rong bridge to the Arabs through the large and virile Christian Arab community in the Middle East. The western church is tied together with those Christians in the World Council of Churches and various other fraternal relationships, fellowships and endeavors. Admittedly and regrettably, the western Christian community has been too ignorant and too unrelated too long to this sizable and significant Arab Christian community; but all this has changed, as with the Jews, in recent years. Christianity's center positron, historically speaking, among the three monotheistic faiths originating in the Middle East may be another asset, inasmuch as the Christian religion is in position to converse with both Judaism and Islam. The position is crucial in terms of influence in both directions and can serve both to enlighten and darken. That the western Christian influence has often been negative has been documentedby Merlin Swartz when he says: "We in the West must remember, however, that we have little right to stand over either the Arabs or the Jews in superior, patronizing judgment,: for the root of the current dilemma is precisely that both Arabsanti Jews have learned too much and too well from the West." Swartz was specifically referring to the deity-sanctioned religious nationalisms and holy wars that Jews and Muslims have carried from Christians. But if there has been one kind of learning there is no reason why there should not also be another kind. Regrettably, Christians have had, all their pretense to the contrary notwithstanding, very little to teach both Jews and Muslims. To make maximum use of their present conversational opportunity, therefore, Christians themselves will first of all have to do the most learning and, we might add, unlearning. History and historical theology suggest the need for nuuiifications, if not reversals, of Christian thought in a number of areas, for there have been serious distortions. 1.The God whom Christians have named has not alwaysbeen the highest God. The Crusades probably remain the best classic example of' mistaking the misguided ambitions of religious; zealots for the highest mandate of the highest God, but the same can be said of' many lesser Christian crusades both before and after. It is a fact of human cultural history that man's thoughts and deeds have too often been implicitly accepted as the highest expression of the divine will. Indccd, if it should be suggested that God's promise to Abraham was in large measure the normal ambition of an enterprising and devoted Fertile Crescent patriarch, who attributed the calls within him to God, history would offer some understanding for that position, Similarly, the slaughterings by the children of Israel, allegedly authorized by God, were dictated not by the highest God but by God reduQed to a tribal deity in the minds of Israel. whom they called the Lord God of Israel. Christians too have done this more often than not, and gone forth to battle with the Russian, French, British. German, and American gods. However, if they want to be light n a dark world, they will have to seek a higher God. Without such a -God. Christians cannot possibly make a contribution toward peace in the Middle East. Nor do they have anything to say to Muslims or Jews whose Allah and Yahweh have sometimes - not always - demanded a higher morality and been a higher God than the Christian deity. 2. The Christ the Christians have nanied or deified was not nhwuti's the divine Christ. In the third and fourth centuries Christians felt it necessary to defend their faith by expressing its cardinal doctrines in creedal form, The motives for this defense were quite -noble, but the consequences were disastrous because the manner of defending the statements often became a denial of the very Christ they confessed.At the time that Christians began in their creeds to uphold the deity of Christ. they began in their deeds what the divine Christ would least have tolerated. He who expressed his divinity by dying for his enemies now had to observe how his followers persecuted his enemies in the name of deity. Anti-Christs were identified on every hand, among the Jews, Muslims, and Communists, and the Christ who came to save the: anti-Christian world as a suffering servant carrying a cross, now went Out to save himself as a crusader with creeds and swords. Christians wondered why Muslims and Jews could not accept this Christian Messiah. They wqre obviously expecting too much. How could Jews and Muslims accept him whom the Christians were themselves not fully accepting? Jews and Muslims, of course, have been equally guilty, for they too did not accept the messiahship or the highest moral insights of their own religions. 3. The chosen people the Christians have identified were not always the 'chosen' people. The earliest and also the later clashes between Jews and Christians were largely due to the religious rivalry arising out of the claims of both groups to be the chosen people. In the process both distorted the concept. The Jews claimed to be chosen just because they were Jews, and the Christians claimed to be chosen just because they were Chrisfians. In the eyes of God, both probably lost their chosenness to the degree that they insisted on it, in the way they insisted on it, and that is why he turned to raising up children from the stones in the desert. As John the Baptist, so called. explained to his racist contemporaries: You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruit that befits repentance, and do not presume to say to yourselves, "We have Abraham as our father": for f tell you. God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham (Matt. 3:7-10). Christians have claimed chosenness both for themselves and, at the nationally convenient moments, for the Jews. They have also applied it wrongly to their national communities, thus contributing to racist nationalisms and Herrenvolk (mast'e'r race) concepts, particularly in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Chosenness does not depend on race. There is no chosenness where chosenness or potential chosenness is denied to others. There is no Qhosenness where there is no choosin. Nor are there any people of God where the Lord is not God. 4. The Iloly, lland and places named by the Christians were not always holy land and holy places. As the history reports, the early Christians were not preoccupied with holy soil and holy sites. They did relate God to nature, but they saw this relation as equally appliCablC to all places. Palestine was sacred by association, but pilgrimage was not a necessary duty of the church, and its imperatives about Jerusalem were valid and applied to all cities everywhere. Christians felt called to make the entire world a holy place, and, as The Epistle to Diognetus said: "Every foreign land is their fatherland and every fatherland a foreign land." This position or attitude changcd with Conataniinc and Ills successors, and Christians adopted the pagan practice of ,iving sacramental significance to particular sites. The bloody Christian crusades, the religious political pilgrimages, the excessivcLy commercialized tourism, and western efforts to internationalize Jerusalem, when the olrl internationalization of colonialism was fading, are all a consequence of a misplaced preoccupation with holy places. And unholiness was also a consequence. The partition of Palestine made the Holy Land unholy in the same way that the original division into two Hebrew kingdoms had unholy consequences. Holiness is not primarily where Jesus once walked but where he is walking today, not where he once bled but where he is bleeding today and where he is coming alive today. Christians, especially western Christians, should renounce their legal and spiritual claims to any holy places in Palestine, turn all their outposts, their hostels and garden tombs over to the natives, and proclaim to all the world that Christ and Christianity are not dependent on them for meaning or for survival. This act of renunciation could help other religions to reconsider their excessive preoccupation with the holy places and with their holy acts of religion, and to return once more to the essence of true religion: Bring no more vain offerings; incense is an abomination toire. New moon and sabbath and the calling of assemblies1 cannot endure iniquity and solemn assembly. Your new moons and your appointed feasts my soul hates; they have become a burden to me, I am weary of hearing them. When you spread forth your hands, I will hide my eyes from you: even though you make many prayers, I will not listen; your hands are full of blood, Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doings from before my eyes: cease to do evil, learn to do good; seek justice, correct oppression: defend the fatherless, plead for the widow (Isa.1:13-17). 5. The so-called kingdoms of God, identified by Chrislicttts, have not been the kingdom of God. The social order of the early Christians emphasized spirituality and universality. Their kingdom was different and larger than any kingdoms oF the world. The kingdotn of God rcpresentcd relationships and had goals that transcended earthly kingdoms. Caesar and his empire, they believed, represented a loyalty too limited. This attitude too changed with Constautine, in whose mind the empire of the Caesar and the kingdom of the Christ be-came almost synonymous, and that thinking carried over to Christians. Subsequently they became some of the most avid religious nationalists that European and North American states have known. After Constantine it was inevitable that Christians should attempt to establish a"Kingdom of Jerusalem" sofftewhere, if not in Jerusalem (though that possibilily was not destroved with the failure of the Crusades) then in Rome (where a kingdom has been established), or in Moscow (the Third Rome), Berlin (headquarters for the millennial Reich), Paris, London, or Washington. These latter kingdoms extracted from the Christians attachments, loyalties, and sovereignty acknowledgments that were intended for the kingdom of God. The results were the warring nationalisms of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which Christianity nurtured and supported. The religious intensity of Arab or Jewish nationalism is, as Merlin Swartz has reminded us, tile contribution of the western Christian statcs. To expect transcendence in Judaism and Islam is to expect more than Christians themselves have achieved. Therefore, if Christians hope to make a contribution to long-term peace they will have to rethink and reverse themselvcs on the kingdoms in favor of a world federalism and the greater kingdom of God. 6. Most, if not all, of the holy wars were unholy wars. Muslims are not tile only religious people who believe in jihad or holy war. The Christians have fought many holy wars, many more than the Arabs, and all the present military action in the Middle East proceeds on the assumption that God or gods have sanctioned or even demanded it.But a holy war is really a contradiction in terms. Christians have always believed that the jihad was incompatible with God. The Muslims had a similar conviction about the Christians' crusades. These crusades were against Allah, not for him. Similarly, the J>ws have recognized only their own wars as holy, no matter how bloody they once were or how flaming they are now. What all three religious peoples have not recognized is that their own wars are as unholy as all the rest, and peace will not come to the Middle East until they apply to their own wars the condemnation they ustially reserve for other wars. Christianity must renounce the concept of holy warfare, first for themselves and then for the Jews and Muslims, if they are going to make any contribution lo peace. 7. The Bible that Christians have read was not always the Word of God. Christians will have to restudy their holv book, for all their misrepresentations of God. Christ. chosen people, holy places, kingdom, and holy wars, have been read out of the Bible. How this can and does often happen and how the poetic literature of the Bible lends itself to various uses can be seen from a 1969 advertisement in the New York Times Mctgal-irre for Sabra, a liqueur imported to North America from Israel." Introducing the ad were the words of Isaiah 27:6: "And Israel shall blossom and bud, and fill The ace of the world with fruit." Even the most prophecy- or nationalist-minded interpreter of the biblical literature would agree that such a literal application of lsaiah's poetry represents a complete misreading of the prophet. But why should the words not apply to liqueur, if words have been similarly misapplied to racism, nationalism, militarism, and Zionism-all of which have turned out to be a much stronger drink for Judaism and the Middle East than Sabra will ever be to the world? Some biblical scholars, seeking to understand the ancient and modern events in the Middle East, have brought together all the references in the Bible to Jerusalem, Zion, Israel, promised land, etc., and constructed from them elaborate schemes of prophetic fulfillment. What these schemes overlook is that the same words either in biblical or extrabiblical usage did not always have the same meanings and could not always be equated. Zion, Jerusalem, and Israel, for instance, sometimes mean literal-historical places, but often they are used poetically and symbolically to communicate universal moral and spiritual truths. Christians should remind themselves that the various prophetic schemes that have had credence within the Christian community all arose in specific political contexts in which Christ and anti-Christ were related to the political powers of the day struggling against each other."' The schemes changed with the changing of the powers. At the moment ivaDy Christians see Christ allied with America and Israel and the anti-Christ with Russia and the Arabs. One would think that before such a scheme is taken too far one would at least consult Arab and Russian Christians whose devotion to Christ, as well its their national feelings, have at least as much validity as those boasted in the West. This is not to say that there is no prophetic content in the Bible, but the prophecy has been of a different order than has been commonly understood. The prophetic direction of the scriptural message is toward the universalization not the tribalization of God, toward racial inclusiveness rather than exclusiveness with respect to the chosen people. The promised land is extended rather than narrowed. Its people are increasingly known for their moral righteousness rather thanfor their military might. "Jerusalem" becomes the eternal city of God and of luan rather than the temporal city of a nation or tribe. To read the Bible in the other direction, as it were, is to misread it and to contribute to the Middle East conflict rather than to resolve it. There are many specific problems one could discuss. We shall consider a few of these in order to illustrate how necessary the rereading actually is. One problem has to do with the intended beneficiaries of the land of promise. The normal answer, of course, is that the promise was given to Abraham and his sons. But who are these sons'? There are two broad interpretations: the literal-physical interpretation and the symbolic-spiritual interpretation. If the literal interpretation is to be followed, there still are two possibilities. In the first place, Muslim and Christian Arabs see themselves, at least to a considerable extent, as descendants of Abraham through Ishmael (tile first son of Abraham) or Esau (the other son of Isaac), and thus as having a claim to the promise. It may be said that Ishmael was excluded in preference for Isaac.. but Arab Christians can present a good scriptural case for including lshmael. If tile descendants of Ishnael are not to be included, then, according to the literal interpretation, one would still be forced to ask whether modern Jews are the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Earlier in this narrative it has been suggested that many of the modern Jews are by no means racial descendants of Abrahana's family and that the modern Jew by Jewish definition is a Jew because of his mother. Racially the Arabs may be more purely Abrahamic than the Jews, although one must nQt forget that Arabs too are racially a heterogeneous group. If one follows the spiritual interpretation, there also are several possibilities. In the first place, the spiritual sons of Abraham can include all those Jews. Muslims and Christians who are identified with the monotheistic religions based on Abraham. In a more specific spiritual sense, Christians have seen the new community founde~ki on Christ as the new Israel. Whatever emphasis is followed, Abraham's "descendants" are those of Iikeminded faith rather than those of similar flesh.Once the true "descendants" of Abraham have been identified, the geoV~raphical dimensions of their inheritance can be seen in a different light. The land promised to Abraham and his descendants, it has been said, extends from the Nile to the Euphrates (Gen. 15:18). These references to borders, however, have symbolic rather than literal meaning, and one should recognize that for Abraham they represented the normal limits of his world's geography. His vision for a promised land was worldwide. If one gives the passagc in Genesis a literal interpretation, it presents two problems. If, Qn the one hand, one applies it to the Land of Israel, it follows that the State of Israel must expand, as most Arabs think it intends. To them, of course, such further military advance is unthinkable and humanly unjustifiable. On the other hand, if one applies the promised land to all of humanity as one should. because even Abraham's dream envisaged blessing for all nations, then the Nile-to-theEuphrates land i5 much too narrow. For Abraham, it must also be remembered, the pronhise of blessing had as much to do with the revealing of a higher god as it had to do with the sighting of new land. Besides, the promise was as much a promise given as a promise received. There was no promise without a covenant, and the moment Abraham heard "to your descendants will I give this land" he also understood "walk before me, and be blameless" (Gen. 15:18). All of this means, of course, that it is foolish to talk about promised land purely in terms of acreage or territory as it is to talk of chosen people in terms of flesh or race, or as it is to talk of God's coming society fn terms of a particular hill or buildings, such as the city that once belonged to the Jebusites. What does all this mean? Does it mean that Palestine is not the promised land and that Jerusalem is not the Holy City? Does it mean that the Jews are not the chosen people, nor are the Christians and the Muslims? The answer to all of these questions is both yes and no. The answer is certainly no if we consider all of these mat~-ters in a legalistic way. There are no chosen people and no promised land anywhere in this world without a covenant with the highest God, and this includes stewardship, justice, righteousness, and morality. There is no holy city, no matter how many holy places there may be for any number of re-ligions, if God does not dwell there in spirit and in truth. There also is no just claim to -any land where such a claim means a denial of a similar claim to one's fellowman. America does not belong to white Americans if it does not also belong in an equal way to Indians and Negroes. Palestine does not belong to the Jews who are now there if it does not also belong to the Arabs who once were there, and it does not belong to these Arabs if it doesn't also belong to those Jews.Thus to minimize the present status of the land of promise and the qualifications of all the self-chosen chosen people is not to say that Palestine cannot or should not or will not be a land of promise in the twentieth century. The Middle East is still a land and water bridge between three major continents. It still is the place where the three major monotheistic faiths have their roots and symbols. Palestine and Jerusalem are still a focal point for much of huntanity. This land can flow with milk and honey. Its foremost city can be the source of truth and righteousness. One can, therefore, sympathize with the late Jewish philosopher Martin I3ubcr, whose hope for Israel was that it will offer to the world a new way of life and that Jerusalem may yet become a substitute for other world capitals such as Moscow and Washington. The Lord knows how badly the world needs the model for a new way of life and a new Jerusalem, "a Zion radiating its righteousness across the whole world."" The Jcw~, who have given and still give much to the world, could once again contribute to such an alternative, as could the Arabs, whose genius is blessing the world in ways too numerous to mention. Christians, who discovered in Jesus the way, the truth, and the life, may also not be excluded. Now, however, one can only say "a plague on all your houses." Unless the Judaism of present-day Israel and Israel itself undergoes a transformation, unless also Islam experiences a conversion, and unless Christianity is reintroduced to the true Christ, there will be no chosen people and no promised land. If there will be, we will probably find them in another place. In the same way that God can raise up children unto Abraham from stones, he can find his chosen people today where he will. He can create a promised land where he will, and he can turn any hovel of a village into his holy Zion. As things stand at present, neither Jerusalem, Moscow, Berlin, London, Paris. Cairo. Rome, or Washington is receptive to the establishment of his holy hill. II. THE CONFLICT SITUATION Now that we have discussed sonic aspects of the Christian involvement and identified some of the rethinking that is neces-sary if Christians are to make a real long-term contriflution to peace in the Middle East, we may look at the situation itself and then consider some more specific responses. These responses, it must be emphasized, will have real significance only in the context of the new heart and the new frame of mind set forth above. The prophecy that most needs to be fulfilled among Christians as well as among Jews and Muslims is the one- that came through Ezekiel: "A new heart will I give you, and a new spirit I will put within you; and I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh" (Ezek. '36:26). In our look at the situation, then, we must first acknowledge that the Middle East confronts the world with a conflict of the gravest proportions. As horrible and problematic as are the war in Southeast Asia and the recent civil war in Nigeria, one could visualize these conflicts ending without engulfing the entire world. The Middle East conilitit, on the other hand, shows no signs whatsoever of coming to an early end.The traditional kind of ending to conflict, a decisive but regionally contained military finish, is not possible for the foreseeable future. Israel can and probably will win additional "six-day wars" over the Arabs, but it cannot possibly crush them. Both Arab humanity and geography are too large for such a victory, and Arab stubbornness is too great for an easy surrdnder. By military measures the Arabs have been "defeated" several times, but they have not acknowledged defeat and bowed to the victor. Consequently, the victor in the Middle East is helpless.The Arabs, on the other hand, cannot in the near future overcome Israel. Although the West tends to overemphasize Arab disunity, disorganization, and inefficiency, it is undisputed that Israel is strong in all those areas in which the Arabs are weak. Thus the Arabs too are not in military position to end the conflict , if a military end to it can be visualized at all. Even if one side or the other could at this time attempt a final military decision, there would be so much opposition from world public opinion that the attempt would be severely handicappe.cl. Indeed, the opposition would be so -reat that big-power interv,ntion would be the undoubted result, and this in turn would lead to a conflagration of unprecedented maenitude. The word Armageddon would not be too weak to describe the ensuing holocaust. Such an international disaster will indeed be the end of the Middle East conflict, if peace is not established soon. Unless some agreements are reached between the contesting parties, it is just a question of tine efore the time bomb in the middle blows up the entire world. Before that happens we face a shorter (perhaps a decade) or longer (perhaps a century or more) period of intermittent warfare with the hot conflicts becoming increasingly hotter and the cooling off periods increasingly shorter. All of these wars and the final war may be viewed as a judgment of God on all that man did to cause the conflict and on all that he failed to do to avoid it. Sometimes the situation appears to be so grave, the trendsso irreversible, and the causal factors so deeply rooted that little can be done, it seems, to avoid the ultimate catastrophe. Yet, we cannot give up hope that mail will yet judge himself, recognize his wrongdoing, reverse the trends, and make peace with his fellowman. With an Israeli writer, we can express both realism and optimism: I am an optimist. I believe that nothing in history is predetermined. History in the making is composed of acts of human beings, their emotions and aspirations. The depth of bitterness and hatred throughout our Semitic Region seems bottomless. Yet it is a comparatively new phe-numcnou, the outcome of the recent clash of our peoples. Nothing like European anti-Semitism ever existed in the Arab world prior to the events which created the vicious circle. We have seen, in our times, Germans and Frenchmen cooperating, if not loving each other, after a war which lasted for many hundreds of years and whose bitter fruits are deeply imbedded in both German and French culture, We are witnessing today the beginnings of an American-Soviet alliance which would have been unthinkable only a dozen years ago. Before there can be a beginhing in the desired direction, however, there must be a clear recognition of what factors or causes are central to the Middle East conflict. We must, therefore, return to the claimants and their claims, and identify the basic or what we might call prior claims. The following layers in the conflict require consideration: The United Nations The Super-Powers - US and USSRThe Arab States and Israel Judaism, Christianity, and Islam The Palestinian Arabs and the Israelis The several layers or dimensions in the Middle East conflict complicate the issue exceedingly, but it is most important that we assess the situation as it is at the beginning of the 1970s. Where we begin determines where we come out. What central focus we give to the problem has bearing on the focus of our solution. How close we come to the source of the cancer may determine the success of treatment and surgery. Our reference to the United Nations is not to be seen as running parallel with the listing of other parties to the conflict, yet we may not pass this power structure by. Ideally, the UN is the indispensable. arbiter and medi7tor in the conflict, giving its car to all parties in the dispute and making decisions on the basis of the UN Charter and established international law. The UN has been in the past, and will need to be in the future, a neutral police force to enable orderly implementation of the international will. In the meantime, the relief agency of the UN (UNRWA) i& providing essential, though minimal, services to the refugee community, and those programs should be undergirded. The United Nations is by no means ideal or perfect as an instrument of international law, order, and justice, and it too stands under the judgment of God. Indeed, the UN may have made some very fundamental mistakes in its early years with respect to the Middle East. But the UN represents a step - at present the world's biggest and best step - in the direction of the vision of Isaiah, who saw the nations of the world surrendering their sovereignty in favor of a higher authority and a superior will: It shall come to pass in the latter days that the mountain ofthe house of the Lord shall be established as the highest of the mountains, and shall be raised above the hills: and all the nations shall =flow to it, and many peoples shall conic, and say: Come, let us go up to the mountain of the Lord ... they snall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any niurc (Isa. 2:l-4). The United Nations has difficulty living up to its own ideal role, because, like its predecessor, it tends to be used by the big powers to their advantage. In the same way that the League of Nations did the will of France and Britain, so the United Nations largely represented the will of the victorious European and North American nations of World War II, particularly in its early years. The position of these nations, for instance, prevailed over the legitimate will of the indigenous Middle East peoples and nations in 1947. Even the idea of the internationalization of Jerusaleln, advanced in 1947 and again in 1967 as a good way of recognizing the universal interest in and character of this famous eity, was a western idea, which could be traced back to the carly nineteenth century, when the British wanted and needed an outpost in Jerusalem. The western nations have always reached eagerly for every opportunity to have political, religious, commercial, or military stations all over the world; and, as the colunial era passed in the Middle East, internationalization appeared to be a good way to accommodate the continuing western interest. 'To the Arab world, however, internationalization of a city belonging to them was an idea as bad and as unacceptable as the internationalization of London, Paris, and Washington would have been to the British, French, and Americans, respectively.Powers, States, and Religions This leads us to consider more pecifically the involvements of the big powers. There are at least tour, though the earlier interests or Britain and France, which reached their recentpeak in the Sinai-Suez War of 1956, have now definitely given way to the two super-powers, the United States and Soviet Union. Since 1967 there has been a tendency to look upon these two nations as the main causes of the conflict and also as the only solutions. Late in 1969 some Arab states announced that they looked upon the United States as their number one enemy. Similarly, the Israelis have frequently blamed Communist interference in the Arab world for the lack of a peace settlement. The two big powers are obviously committed to the Middle East, and their presence both as cause and solution to tile problem, should not be underestimated. But neither should it be overestimated, as has frequently been the case. In spite of the interests of both the United States and the Soviet Union, the Middle East conflict cannot and should not be reduced simply to another US-USSR confrontation. Nor should it be identified purely as a struggle over boundaries between Israel and the respective Arab states, as is fre-quently done by the popular press. The various Arab states are, of course, in a state of war with Israel, especially those who claim territory that Israel now occupies, namely: Egypt (Sinai and Gaza), Jordan (West Bank), and Syria (Golan Heights). Yet, one could visualize all of these states making separate peace treaties with Israel after certain border adjustments, if the territorial conflicts were not overlaid by a more basic quarrel. After all, they all did sign separate armistice agreements in 1949. Beyond the quarrel over territory, the Arab states and Israel, respectively, symbolize the conflicting cultures of two peoples. But as serious as the disparity between the two is, it is not at the moment the fundamental issue which is firing their respective nationalisms, and we must take a closer look at what is really burning. The oil on the fire has sometimes been identified as religion, and consequently the- conflict has been seen as a war between Judaism and Islam. Islamic appeals for a holy war following the 1969 burning of the Al-Aksa mosque in Jerusalem and Jewish reaction to the Arab maltreatment of the holy places of Judaism lend some support to this theory. And it is true that both sides appeal to holy literature and other sacred symbols in support of their causes. Yet it would be a mistake to see the Middle East problem primarily as a religious war in the sense of an Islam-Judaism confrontation, and that for several reasons. In the first place, the Arab world is not all Islamic. There are many Arab Christians in Egypt, Palestine, and Lebanon who feel exactly as their Muslim Arab brethren do. Secondly, not all the Islamic world is Arabic, and non-Arabic Asian and African Muslims do not enter into the Middle East problem with the same intensity, if they enter it at all, as do the Arabs. Finally, Judaism as a religion does not appear to be a primary motivator with a large majority of Israeli Jews. The Middle East conflict at its core is not another US-USSR confrontation, not a test of military muscle between Nasser and Dayan, and not a quarrel between Muhammad and Moses. Rather it is a contest for control of the same parcel of land (Palestine) by two peoples. namely, the Jews (mostly of European origin) and the Palestinian Arabs. Both of these peoples have been terribly wronged in the past. To be sure, both have won the support of, and been spon-sored by, one or more of the big powers, Both have appealed to their religious heritage for direction, strength, and legitimacy. And, to the extent that the Arab states have spoken and fought for the Palestinian cause, the struggle has taken on the shape= of a contest between sovcrcign Arab statcs and the State of Israel. But at its root, the quarrel results from the incompatible claims of two peoples for the same parcel ofland. Both call it their homeland. To the Jews,_ "'ho __ have gained- it, the new name_ for the homeland is security. Forthe Arabs, who have lost it, it.could very well. be called justice. For both, the land, in_ additiqn to justice and security, spells fulfillment.The Jewish need for security, of course, goes back to the European experience of many centuries of second-class citi-zenship and persecution. Whatever the Jews themselves may have contributed to the discrimination, persecution, and extermination policies of which they were the target, there can be, and must be, no doubt about the fact that they have been terribly wronged. It should never have been necessaryfor the various European states to pass special laws giving Jews the full rights which were theirs by birth. To the extent that history made special laws necessary, they should never have been delayed until the middle of the nineteenth century. These rights, having been granted, should not have been rights only on the law books but also in the hearts and minds of the people. France, England, and the United States should not have found it necessary to find a home for the Je~-vs outside of their own countries, while they themselves had still not fully accepted Jews or welcomed their persecuted brethren from elsewhere in the world. In eastern European countries the bloody pogroms can never be excused no matter how well the national historians may succeed in explaining them. And Germany's "final solution" for the Jews in the twentieth century is an injustice and horror too great to describe in words. Admittedly, many Jews too were not without social guilt, but that is quite beside the point in the light of the wrongs that were done against them by European populations and their rulers, most of whom supposedly enjoyed the enlightenment of the Christian faith. As the Christian nations in Europe and America recognized, belatedly, the wrong that had been done, they tried to make amends by redressing the wrongs committed a0ainst, and winning the favor of, the Jews. These efforts in turn produced the church theologies and the national and international policies that granted to the Jews their own territorial state in the twentieth century. In the process of serving the Jews, the western peoples worked out once more, perhaps subconsciously, their traditional hostilities against Islam and the Arab, no longer by overt crusades against him, but by ignoring him and treating him as a non-entity. One might say that an old anti-Semitism directed against the Semitic Jews now became a new anti-Semitism directed against the Semitic Arabs. As the old anti-Semitism terribly wronged the Jews so the new anti-Semitism terribly wronged the Arabs. No six million Arabs were exterminated, but their humanity was bitterly offended as slowly but surely several million were pushed into the desert and kept there, not by gas ovens but by the fire bombs of napalm. The surprising and shocking part was that the survivors of the gas ovens were now the administrators of the fire bombs. As Arnold Toynbee has written:The Jews knew from personal experience what they were doing; and it was their supreme tragedy that the lesson learned by them from their encounter with the Nazi Gentiles should have been not to shun but to imitate some of the evil deeds that the Nazis had committed against the Jews." This then is the central problem of the Middle East: the attempt to redress a wrong committed against the Jews produced a similar wrong against the Palestinian Arabs. The very promises made by the big powers and the United Nationss that oave the Jews their homeland denied the Arabs theirs. The acts of the Zionists that restored the Jews robbed the Arabs. 'File tragedy of tile robbery was compounded by the fact that the victims of the new Jewish self-assertion were not the ouilty-o1'-persecution Europeans, but the relatively innocent Arabs, who for centuries had, with few exceptions, provided a haven for certain homeless and insecure Jews. But this is not to say that the Arabs were in no way re-sponsible for the human tragedy that befell the Palestinians. Absentee Arab landowners, who disregarded the rights of tenants as they sold their land for material gain, and ambitious Arab rulers, who were hungry for personal power and resisted the social revolution so needed in the Arab world, must share some of the blame for the maltreatment of the Palestinians. The biggest abusers by far, however, were the British, the Zionists, the Americans, and the French, followed by the Russians. The big powers felt that if they pushed out another big power, namely, the Ottoman empire, they were free to do with the area as they pleased after the manner of former empires. Sharing the blame with the western powers are their Christian communities, who lacked the respect due the native Middle East populations and their faiths at the most crucial times. The Zionists, encouraged by the stance of the Christians and the policies of Christian nations, promoted dreams and visions that discounted the native population, much in the same way that European immigrants to North America through the years discounted the humanity of the native Indian and Eskimo populations. The Zionists did not ask about the rights of the Arabs. The League of Nations allowed itself to be blinded by the Zionists and the big powers, which had material interests in the Middle East, all on the assumption that the Arabs were not aware, mature, alert, capable, or even there. The Palestinians patiently endured the nonrecognition of their humanity and its basic rights at a time when the rights of the people around the world were being recognized, and when all the colonies were being decolonized. Considering the wrong done against them, their passivity and endurance was remarkable, even when we acknowledge that their political and military handicaps left them little other choice. It is wrong, therefore, to say today that the Palestinians understand only the language of force. Their taking up arms is, much more an indication that the Zionists and the big, powers understand only the language of force. For twenty years, from 1947 to 1967, the Palestinians were relatively pacific, waiting for the Arab states to do what they said they would be doing, and waiting for the United Nations to implement its resolutions. When all of these failed, the Palestinians organized themselves and turned to arms as a way of achieving the recognition and the dignity they had long been asking for. We must recognize, therefore, that the Palestinian struggle for the liberation (as they call it) of their homeland is at the root of the current problem. It is this cause which is now dominating the politics of the Arab states. It is this cause that has won massive support, not only from Arab states but also from several of the bigger powers like the Soviet Union and to a lesser degree France aud to a still lesser degree Britain. Israel's greatest security problem is not now (if it ever was) any one of the Arab states or all of them together but rather the Palestinians and their commandos seeking a return to their homeland. In this return they are demanding and receiving the support of the respective Arab states. Admittedly, some of these states, as they cooperate, have very much in mind their own powcr interests and border grievances, but in the Middle East conflict these are secondary to the more basic Palestinian cause. That Palestinian cause will remain a cause as long as injustice is continued. The western powers have, ever since World War I, proposed Middle East solutions that bypassed or minimized the injustice. They hoped, no doubt, that the Palestinians would adjust to the new order of things in the same way that millions of displaced Europeans adjusted to new situations. But the Middle East injustice would not be adjusted away, and for the westerner to demand that unwilling Arabs adjust to injustice was only to perpetuate the injustice. As a child of refugee parents who fled the Bolshevik Revo-lution and made a new home in Canada, this writer too wonders why the Palestinians did not express readiness to resettle. Otherwise, however, he is in no moral position to make the suggestion that they do, partly because the western immigration door is no more open to them than it was to the Jews in the 1930s and 1940s. But how can justice now be done to the Palestinian Arabs without once more threatening the security of the Jews? Admittedly, the situation is complex, but it is not so difficult that nothing can be done. Many peace plans have been advanced by many people at various levels of authority in the last two decades, all to no avail it appears; and one must be a little foolish, a littlepresumptuous, and a little courageous to make additional suggestions. Most of what remains to be said is not new, being simply a reintorcenient of what has already been advanced by others, including the former Commissiongr-General of UNRWA, John H. Davis. Speaking about the "evasive peace," he suggested the following guidelines: The policy adopted must hold forth real promise of bringing an end to confiictt which means that it must be both equitable and possible of implementation; it must bring jus-tice to the Arab people for the grave wrongs that they have endured that Israel might exist, and protect their rights and their way of life for the future; and it must protect the people in Israel against wrongful acts and persecution and, in so far as possible, preserve for them their traditional way of life. Also, it is imperative that the welfare of the people be put above that of institutions and states when the two are in confiict. As a general guide, past United Nations resolutions should prove helpful, since their weakness has never been their content but their lack of implementation. Furthermore, the members of the United Nations have already reached agreement on them. What can western Christians do toward that end? The most important contribution has already been dealt with at length, namely, adopting for themselves and offering to the world new ideas about God, the Messiah, chosen people, holy places, the kingdom, holy wars, and promised land, for it is the old ideas - the distortions of Christian faith - that have brought so much tragedy. In other words, let the Christians, first of all, accept their Messiah and become Christians, and they will have made their most important contribution to peace. The new spirituality will, of course, require outlets in a new policy. This policy will have to go beyond the two that Christians have always supported, almost without reser-vation: preaching and shooting. It may seem incredible, but between these two extremes Christians have had difficulty visualizing and supporting other strategies. Let us, therefore, propose two others between the two extremes. The one, which we will call "prophesying," has often been disparagingly called "getting involved in politics," and many conservative Christians have rejected it because it was too realistic and not sticking close enough to the gospel. The other, which we can call "cross-bearing" or "peace-making," has been rejected, usually by the same people because it was not realistic and practical enough as, for instance, was shooting. Essentially, prophesying has to do with the bold proclamation of the will of God in very practical and relevant terms in high places and low places. Adapted to the modern situation it has to do with giving God a chance at mass public opinion. It requires confronting the decision-makers at all levels with respect to the priority claims of God, with righteousness, justice, security, and peace. It means getting involved in politics the way the Old Testament prophets involved themselves with wayward Israel, the way Muhammad involved himself by challenging the idolatry with the concept of one God, and the way Jesus involved himself.when he announced a new kingdom. Admittedly, the prophetic role requires much insight and wisdom (a political position, if you will), and courage. But if Christians could begin to prophesy to each other first, and then to their societies and to their nation-states, they would gradually prepare the way for the purest kind of prophecy cotning from the church at its most authoritative levels to the highest decision-makers in the world, meaning the superpowers and the United Nations. Eventually, they might even prophesy to Judaism and Islam, but this could only be done if Christians were prepared also to hear Jewish and Muslim prophets. But what may be the substance of the prophetic proclamation, of the Chri-,,tian injection =into public opinion? In general and basic terms the ground has already been cov-ered in the first part of this chapter, but let us now be somewhat more specific: 1. Justice for the Palestinian Arahs. There can and should, first of all, be a full recognition in the West that a great injustice has been done to the Palestinian Arabs and that mostly by the West. This admission, if it were full and sincere, would itself do much to relieve the pressure in the Middle East. A verbal admission of course must be followed by some meaningful action. But to begin with, let British, French, American, and Canadian Christian people admit themselves and persuade their governments to admit the repeated violation of the human rights of Palestinians. Secondly, let Christian people help the Palestinian Arabs tell their story to the world. They have tried to tell the West by themselves since 1919, but they were weak and handicapped, and western ears were learning to respond less and less to simple pleas for justice and more and more to massive propaganda onslaughts and the noise of firearms. It is regrettable that the Palestinian Arabs are now learning the propaganda and military games, but they have turned to this undesirable way of communicating not because they could not communicate another way but because the West would not listen any other way. If Christians would give a fair hearing and fair telling to the Palestinian story, the Palestinians would feel less need to communicate with hijackings and bombings. A third requirement of prophecy is to prevent further expulsions. Early in 1970, more and more Arabs in the occupied territories were being made homeless in the name of Israeli security, while Jewish immigrants were being received at the rate of 150 a day. The 1969 totals were near the 60,000 mark, one of the highest yearly totals. Whatever rights to Palestine these European Jewish immigrants may have, they surely do not transcend the rights of the Palestinian Arabs who are already there and those who are waiting to return from beyond the river. The most elemental prophecy that Christians could give is that which has already been given to Israel by one of its own leaders: Nothing frightens the Arabs more than the idea of the Ingathering of the Exiles. There arises before Arab eyes the spectre of a wave of Jewish immigration, bringing to Israel another ten million Jews, overflowing its narrow frontiers and conquering Arab states, evicting the inhabitants and grabbing land for innumerable new kibbutzin:. There is something ludicrous in the present situation. Zionist leaders, including Prime Minister Eshkol, make visionary speeches about millions of Jews who will soon arrive on the shores of Israel, fulfilling the prophecy of Zionism. To an Israeli audience, knowing the reality, this is the sort of wishful thinking by which an antiquated regime tries desperately to preserve its obsolete slogans. Yet, to millions of Arabs these speeches sound like definite threats to Arab existence, threats made even more terrible by Israel's manifest military superiority. Fourth, while preventing further expulsions of and injusticesto Arabs is a difficult task, the return of those who have been away from their homes, most of them out of the country for over twenty years, is vastly more complex. Their country is still there, but it is no longer what it once was, and in most, if not all, instances their homes are no longer waiting for them. Physically, however, the country is in position to receive them just as easily as it can accommodate any number of Jews. The least that can be done and should be done is to affirm with the United Nations that the Palestinian Arabs have a right to return or to receive reparations, whichever may be their preference, and to facilitate such return and reparations. We should not say to the Arabs, as we have so frequently in the past, that they should give to the Jews a small share of the vast Arab geography. The Palestinian Arabs had only Palestine, and we might as well say to the Rhodesian blacks that they should resettle to some other part of the vast black continent and leave a little sovereign territory for the whites. That is the language of imperialism, not of justice. The Arab states and Palestinian commandos may, of course, not be excluded from the requirements of justice. They may for themselves not see any alternatives, but they should at least be reminded that guerrilla activities have already started a vicious circle of terror and counter-terror that will bring additional, perhaps unprecedented, miseries to the Palestinian people: Al-Fatah may claim to be liberating the Arab people but it could very well also spell their end as a nation. The prophecy must draw attention to this possibility. 2. Security for the Jews. This is an issue as great as in-justice for the Arabs, and surely God is as much concerned about the one as about the other. We must understand the Jews of Israel. They came to Palestine in search of security. In Europe and other parts of the world they had been most insecure. Most of the immigrants had relatives who were sacrificed to Hitler's final solution. Now as they are confronted by what they perceive as a threat to their physical survival, they are responding as we would all respond. No people can face the prospect of genocide a second time in a generation. It has been said in the Middle East that the Arab threat to push the Jews into the sea is only propaganda. We must understand the Arab and his language, we are told, because to him the deed has been accomplished when the word has been spoken. Granted that there is some truth to this ob-servation on Arab culture, the prophetic word should include a response to such threatening language. When an Arab voices threats he is responsible not only for what they mean to him, but also for what they mean to his enemies. God does not want the Jews pushed into the sea any more than he wants the Arabs pushed into the desert. Thus, the Christian prophecy must seek the restraint of the Arabs, both as states and as Palestinian commandos. Moreover, we must probably also give attention to the continuing insecurity of Jews in Eastern Europe, even if that insecurity is not -as great as Zionist propagandists would have it,,-' We should make sure that in the United States and Canada they will always find a warm welcome and secufity. It would be wrong to suggest that these too go to Palestine, because we have already concluded that security for Jews in Palestine means injustice- for the Arabs there, and that in turn means insecurity for the Jews. The Jews who have already made Palestine their homeland have a right to stay there, but it would be difficult to accept further immigration until the requirements of justice to the Arabs have been met. Surely, Palestine belongs more to the Palestinian Arabs in exile who want to return than to the eastern European Jews who have never been there. It has been said that the security of the Jews as a people depends on the sovereignty of Israel as a state. Indeed, that sovereignty was allowed by the international community on the assumption that it meant security. That assumption, however, is becoming increasingly questionable as time goes on. To the Palestinian Arabs security for Jews and sovereignty for Israel were always two separate questions. They were always prepared to guarantee the former but never to accept the latter. Consequently, they opposed Jewish immigration to the extent that it pointed to the establishment of a Jewish state. When the Zionists insisted, as they still do, that the security of their people and the sovereignty of the state were one and the same thing to them, then they also began to mean the same thing to the Arabs. At that point the Arabs began to say that the destruction of Israel as a state could require that the Jews as a people be driven into the sea, just as the creation and expansion of the state required the driving of the Arabs into the desert. This will not happen soon, but eventually it could happen. In the long run an Israeli state is as insecure in the Arab world as white regimes are insecure in Africa. All who are interested in the security of the Jews in Palestine are, therefore, obligated to prophesy to them about the sovereignty that does not fit, the state sovereignty that militates against Jewish security. Not to do so will mean once more to share in the guilt bf Jewish insecurity. Support for this point of view is to be found not only in a proper analysis of the current situation but also in a review of the ancient kingdoms of the Hebrew people, as well as some contemporary Jewish leaders. As ong Jewish historian has reminded us: The throne of Israel was a precarious post, offering the ruleran average occupancy of 11 years. Altogether nine separate dynasties rose and fell during the 212-year period of its monarchy, one dynasty lasting as little as seven days. Few of the 19 kings who occupied the throne died of natural causes." The Israel of the twentieth century is in many ways politically and militarily stronger than the kingdoms of old, but the perils from without are also much greater. And were there no perils from without, the divisive perils within would loom large, because Zionism has within it the seeds of its own destruction, as much as did the Kingdom of Solomon. For Israel to depend for the security of the Jews on chariots and horsemen seems as foolish now as then. Some Jewish leaders inside and outside of Israel have themselves recognized the dangerous character of the present State of Israel and called for its de-Zionization. Essentially, they have reiterated the warning given by the late Henry Morgenthau, prominent American Jew and Senator, who foresaw the tragic consequences of Zionism already after World War I. Having been sent to eastern Europe by President Wilsorn to investigate the plight of Jews he was fully acquainted with. "the indignities and outrages to which he had been subjected." But he did not see ,Zionism as a"way out of this morass of poverty, hatred, political inequality, and social discrimination." Instead: Zionism is the most stupendous fallacy in Jewish history.... The very fervor of my feeling for the oppressed of every race and every land, especially for the Jews, those of my own blood and faith, to whom I am bound by every tender tie, impels me to fight with all the greater force against this scheme, which my intelligence tells me can only lead them deeper into the mire of the past, while it professes to be leading them to the heights. Zionism is -.. a retrogression into the blackest error, and not progress toward the light. The president of the World Jewish Congress since 1951 and former president of the World Zionist Organization, NahumGoldman, likewise questioned the earlier assumptions of Zionism. Wiiting early in 1970, he suggested that if the State ofIsrael was to bring security to the Jews as people, it would as a minimum have to become a different state, militarilyneutral, territorially less ambitious, and politically more respecting of Arab rights and Palestinian aspirations: The history of the Zionist movement, as of many others, proves that the greatest real factors in history in the long run are neither armies nor physical, economic, or political strength, but visions, ideas, and dreams. These are the only things which give dignity and meaning to the history of mankind, so full of brutality, senselessness, and crime. Jewish history certainly proves it: we survived not because of our strength - physical, economic, or political ~ but becauseof our spirit. Related to the question of security is the question of morality in the context of sovereignty. As we have already seen, theState of Israel is in the nature of an exclusivistic state, again comparable in kind if not degree to the white regimes in Africa. It has proved itself repeatedly to be expansionist. Both of these facts together mean the inevitable subordination of other peoples in the contravention of the UN Charter, of the best in Judaism, and of the rights of humanity. Justice and security for all the peoples who are in Palestine and who have a right to return cannot lie in the rule of one group over the other, but rather in the equal partitipation of all in the government of the total area. Jews can and will find their security if they share their sovereignty, and Arabs can and will find the highest form of justice if, as they return from the desert, they lay down their arms and abandon the notion of pushing the Jews into the sea. Both of these messages to both parties must be part of the Christian prophecy. On both sides we hear people saying that justice (meaning return) for the Arabs or that security for the Jews (mean-ing that they should stay) are impossible. If they are indeed impossible then we must face the ultimate fact that survival is impossible and that Armageddon is inevitable. But if survival is desirable and necessary, and if it is to be made possible, then compromise must also be possible. In some ways this will be more difficult in 1970 than it was in 1920, but in some ways it can be easier, because the passing of time has made it more necessary than ever, as both sides are beginning to recognize. 3. Restrain the Powers and Boost the UN. How is survival possible? How can the minimal necessary requirement (a fra-tcrnal federation of Jewish and Arab states within the land -area of Palestine) or the maximal desirable- requirement (a single state in which both peoples are eq--ual and se=cure) be achieved? It can only be achieved if both parties agree to such a development, and the willingness itself must come by peaceful means. This rules out the usual kind of intervention by the super-powers, which is now advocated by an increasing number of people. There is very little in the imperial history, which we have reviewed, which encourages direct big-power roles as real solutions to regional problems. In their own minds, the big powers may be pursuing the claims of God - and they usually persuade most patriotic-religious folk that they are - when in reality they are working out the claims of empire or the claims of the imperial god, whom they call God. Both of the present super-powers involved in the Middle East have persuaded themselves and their partners and are trying to persuade the rest of the world that their claims are of the highest order. One speaks of the defense of human freedom and the other of human liberation from imperialism. Both slo-ans are about as close to claiming to act in the name of God as one can get. Neither is much different from any of theempires that have preceded it. Both use high-sounding phrases to hide selfish imperial intentions. Rather than increasing big-power intervention, the will of God, as historically revealed, lies• in big-power extrication. The best solution the United States and the Soviet Union can contribute is to cease being part of the problem, which they are as they pursue their economic and strategic interests, as they supply arms to both sides, and as they get in the way of the United Nations, or prevent it from playing its role in the conflict. This is not to say that the big powers must isolate themselves and withdraw from world problems, but unless intervention can be more creative and unselfish, withdrawal would be far better. The United Nations, as has already been indicated, also has it weaknesses, but it is humanity's best step in the direction of achieving peace among the states who need to surrender some of their sovereignties to this higher cause. So let the big powers throw their moral and material weight behind the United Nations, and let the Christians prophesy to that end. As the pen is mightier than the sword, so the prophecy can be much more helpful than the military power to which states too easily resort too quickly. The prophetic contribution to peace does not end, or perhaps even begin, with the spoken word, as important as that word may be for the direction of public opinion and national policy. The bold word must be accompanied, as it always has been in the best of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions, by the sacrificial deed. And this can mean many things, such as the usual varieties of philanthropy for Jews and Arabs. The present Middle East conflict, however, calls for the deed that goes beyond the ordinary and the usual. It calls Christians back to the central theme of their faith, namely, that of a man laying down his life for his friends and his enemies. This is precisely the role to which Christians are being called in today's world. The Middle East situation confronts us with the historical fact that many Jews and Muslims have died or sacrificed their rights on behalf of Christians. Christians can now make a contribution to peace only if they become willing to die and sacrifice on behalf of Israelis and Arabs. And this does not mean going to war on their behalf on either side. Indeed, it is time for Christians to leave all their guns at home. But it does mean entering the arena of war on both sides and sharing the insecurity that the conflict brings. We have in mind an unarmed peace force, consisting of well-trained, well-motivated, fearless, strong, and loving young men and women who would in one way or another absorb the insecurity, fear, and even the blows arising from the conflict. They would stand by and help the Palestinian and Jordanian farmers as they braved the Israeli jets to cultivate their acreage in the Jordan and other valleys. Similarly, they would stand with the Israeli kibbuaim and other settlements being shelled by the Arabs. They would search out and defuse bombs in the market places. They would also help Arabs to dig shelters, warn them of approaching jets, and stand with them in air raids. To many people such a proposal is undoubtedly the height of unrealism, but it is only unrealistic because it has rarely been tried. It could at least be as realistic and effective as policies now being pursued. Many details and technicalities concerning this new strategy would, of course, have to be worked out, hut all of this should not prevent Christians from expressing their willingness to enter the conflict a[ its pliNsicflIv must dangerous points in order to point the \vay to Security and justice. With today's idealistic and sacrifice-minded young people, finding enough volunteers would probably be the least problem to worry about. This approach has application not only to the Middle East but also to other parts of the wo-Tlu, where we might see its relevance more clearly. Take Southeast Asia, for instance. In the spring of 1966 PPresident Johnson pledged his country to an assistance program amounting to one billion dollars to harness and develop the water resources of the Mekong River which begins in China and flows through Laos, ThailancL Cambodia, and Vietnam. It scented to be a very generous offer, but in the light of the thirty billion dollars annually expended since then in military activity, it was a pittance. Yet, if that one billion dollars would have been applied and if all the thousands of Christian Americans who went to Vietnam would have left uniforms and guns at home, and instead gone with overalls and spades to work on that Mekong project under UN auspices, Vietnam and the world would be much, much different today. Not much imagination or prophetic insight is required to conclude that in all probability: many less Americans and Vietnamese would be dead today; the Southeast Asian economy would be in better shape; the political situation would be sounder and stabler; Chinese and Russian influence would be weaker; and American society would be healthier at home and have much greater respect abroad. We must learn the lessons of Vietnam and begin to apply them to other parls of the world where we still have opportunity. As far as the Middle East is concerned, European and North American Christians should leave all their weaponry and hostility at home and persuade their governments to do likewise. For Christians, the holy lands could attain their greatest holiness yet, if they could find, like Chrrt, a way of willingly, innocently, and sacrificially bearing on their bodies tile blows of a warring world. In the shedding of their blood they would find their holiest ground. In the laying down of their lives they would find their most exalted chosenncss. In their equal concern for Jew and Arab they would bi im-, all, irZCludinl~ Lthemselves, closer to the Father. They would, in fact, be establishing the everlasting kingdom of peace of which the prophets spoke and for which the whole world continues to hope. Bibliograpby